Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class Benjamin Sidney Steelman

- Unit: 4th Marine Division, 23rd Marines, 2nd Battalion

- Service Number: 7226157

- Date of Birth: April 28, 1925

- Entered the Military: January 9, 1943

- Date of Death: June 15, 1944

- Hometown: Wilmington, Delaware

- Place of Death: Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands

- Award(s): Purple Heart

- Cemetery: Section F, Grave 883. National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, Honolulu, Hawai'i

Mentored by Mrs. Erin Sullivan

Cab Calloway School of the Arts

2021–2022

Early Life

Benjamin Sidney Steelman, called Sid by his friends and family, was born on April 28, 1925. He grew up in Wilmington, Delaware with his immigrant parents, Esther Kohler and Abraham Steelman, and his younger sister, Shirley Rosalie Steelman. His mother was a homemaker, and his father owned a grocery store in Wilmington. Steelman worked for a time at the Pennsylvania Railroad, and he graduated from Wilmington High School with the class of 1942.

YMHA & Mollye Sklut

Steelman was an active member of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA), which kept him involved in his community. Here, Steelman made a connection with Mollye Sklut, an office manager at the YMHA. Sklut would exchange letters with Steelman during World War II, as well as with hundreds of other Jewish service members from Delaware.

Homefront

Delaware is a small state, but it nonetheless made significant contributions to the war effort. The DuPont Company, a chemical and munitions company in Delaware, produced plutonium during World War II, playing a critical role in the development of the atomic bomb. Additionally, shipbuilding was quite successful in Delaware, and hundreds of ships were built by companies like the Dravo Corporation.

As a result of Delaware’s support of the war effort, the Wilmington community experienced many changes. Curfews were put in place to conserve fuel, and food rations were used to conserve food. Trolleys were stopped so the steel tracks could be used for war efforts. Military bases were established—the Wilmington Airport became the New Castle Air Base, and observation towers were built around Cape Henlopen and other beaches.

Second Street & The “Y Recorder”

Before World War II, Second Street was the center of Jewish life in Wilmington. People came from all over Delaware and the surrounding states to spend the night there. However, Second Street was hit hard by World War II. “The War really was the beginning of the downhill slide of Second Street,” said Lillian Lundy Freid, who lived on Second Street as a child. “Stores closed. Families moved away.”

Throughout the war, the YMHA continued to be an important hub for Jewish social and community activities. The Y Recorder, a newspaper produced by the YMHA, was sent to everyone in the Jewish community. It also became an important connection to Wilmington for many of the service members away from home. Steelman wrote of the newspaper in a letter to Mollye Sklut, “You have no idea how just a little piece of paper can boost morale so much.” Many of the letters Sklut received were published in a column in the Recorder entitled “Dear Mollye.”

Military Experience

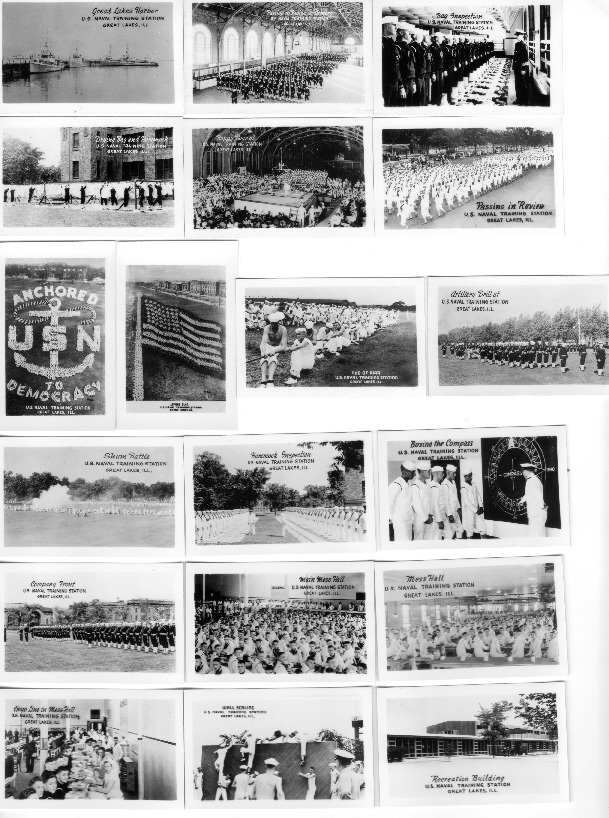

On January 9, 1943, Steelman enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He was only 17 at the time, but he wanted to join the fight despite being under the legal age of enlistment. He first received his training at the United States Naval Training Station, Great Lakes, Illinois. In a letter to Mollye Sklut, Steelman wrote about learning to be a sailor, “My boat training is coming along just fine and I feel like an old salt by now . . . Tomorrow we have a regimental boat match and between you and me, our company is a cinch to take it.”

California

Following Illinois, Steelman moved to Corona, California, and then to Camp Elliott for more specific training. Steelman had family in California and mentioned seeing his uncle, a chicken farmer, and helping him with his work. He wrote, “You know something Mollye I believe I am becoming a better chicken farmer than sailor. When I first came out to California, to tell the truth, I used to be afraid of chickens, but now I help my uncle with a lot of his work.”

In his free time, Steelman also explored the many attractions of California such as the Hollywood Canteen, a club that offered food and entertainment to nearby servicemembers. Here, Steelman got to see many celebrities such as Hedy Lamarr, Joan Leslie, and his “cowboy idol” Roy Rogers.

Rank

Steelman was a Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class in the Navy, a role that attached him to the 4th Marine Division. Because the Marines did not have their own medical corps at the time, sailors like Steelman were assigned. Although Steelman’s role as a Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class did not mean that he was a trained doctor, it was his job to train and travel with the 4th Marine Division and offer what he could in medical support.

Hawaiʻi

After his time in California, Steelman moved to Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. He was constantly on the lookout for familiar faces and managed to catch up with some other men from Wilmington who were stationed in Hawaiʻi.

Steelman also found a new community among service members in Hawaiʻi, and much of that community could be observed in his own tent. In a letter to Sklut, Steelman wrote, “Well today was payday and everybody is sitting around the tent smoking cigars and listening to Bob Hope. They call our tent the camp U.S.O because everybody assembles here at night and shoots the breeze . . . We have fellows who would make Abbott + Costello look like a pair of amateurs.”

Steelman left Hawaiʻi with the 4th Marine Division on June 5, 1944, headed for Saipan. On June 15, the 4th Marine Division arrived at a landing that is often referred to as the “D-Day of the Pacific.”

Battle of Saipan

The Battle of Saipan was a critical point in World War II, and the military success here laid important foundations for the 4th Marine Division to invade the islands of Tinian and Iwo Jima. With this victory and the gain of Saipan, the United States finally opened the path to Japan. This was especially demonstrated on August 14, 1945, when 100 B-29 bombers took off from the island, joining hundreds more bombers from Guam and Tinian to attack Japan. One day later—a little over a year after the Battle of Saipan—Japan announced its surrender.

The end of the war was close, and the United States’ ultimate victory against Japan largely relied on the 4th Marine Division’s strategic success in the Battle of Saipan. Steelman sacrificed his life for this cause on June 15—the “D-Day of the Pacific,” and the first day of the Battle of Saipan.

Eulogy

Steelman was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart for his service. He was buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific and is honored with a cenotaph at the Jewish Community Cemetery in Wilmington, Delaware. Although he was buried in Hawaiʻi with a cross on his grave, his sister, Shirley Rosalie Steelman, faithfully worked to have it changed to a Star of David.

Steelman’s Legacy

While his sacrifice did contribute to the ultimate success of the 4th Marine Division, Steelman’s legacy is much more than that. Above all else, his legacy is one of love—love for his country, for his community, and for his friends and family.

Cyd Weissman, a niece of Steelman, was named after her uncle and remembers feeling his presence throughout her life. In an essay titled “The Legacy of My Uncle’s Name,” Weissman wrote, “. . . at a young age, I found I could actually see Uncle Sidney. I could see him in heaven, seated on a bed, flanked by other good souls like his father. His blue eyes, thick blonde hair, and full lips were recognizable because his pictures dotted our house in my early days in the 1960s.”

Steelman’s legacy of love reaches beyond his life to those who still love and honor him today. Cyd Weissman wrote of Steelman, “Uncle Sidney’s life was a blessing. He was a teen who volunteered early to fight for his country; he was sure he would return home safely; he was shot in the stomach ten days after stepping into action; and he was and is loved and mourned by family and friends. I have been truly blessed to carry his name.” By learning about and honoring his story, we too can honor his legacy.

Reflection

I have always been interested in human connection. When applying to Sacrifice for Freedom®, the program most appealed to me because it gave me the opportunity to experience that connection with a Wilmington veteran who gave his life for his country in World War II in the Pacific. I have learned so much from Sid Steelman and his family, and I am so grateful to have been given the opportunity to work alongside my incredible teacher, Mrs. Sullivan, and share Steelman’s story with the world.

I have met so many amazing people through Sacrifice for Freedom® between our time in Hawaiʻi and the many months of research and preparation leading up to the trip. I have now met educators and historians from all over the world who are rooting for students and actively working to create opportunities for them to grow and learn. Additionally, I have met fellow students who have a passion for history, but who are also looking towards the future with many aspirations. I also had the honor to meet Steelman’s nieces, who assured me that there are still people out there who love Steelman and carry his legacy with him. All of these people, and the impact they continue to make on the world, give me great hope for the future.

Telling the stories of people like Sid Steelman is such a wonderful and important thing, and my experience in Sacrifice for Freedom® has made that clear.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Benjamin Sidney Steelman. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Benjamin Sidney Steelman. U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Benjamin Sidney Steelman. U.S. Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Benjamin Sidney Steelman. U.S. Rosters of World War II Dead, 1939-1945. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Benjamin Sidney Steelman. World War II Jewish Servicemen Cards, 1942-1947. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Benjamin Sidney Steelman. World War II Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Casualties, 1941-1945. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Delaware. New Castle County. 1930 U.S. Federal Census. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Delaware. New Castle County. 1940 U.S. Federal Census. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Hilda Codor. Oral History. Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. Accessed August 17, 2022, jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/items/show/180.

Mollye Sklut. Photograph. Jewish Historical Society of Delaware.

Steelman, Benjamin Sidney. Benjamin Sidney Steelman, Dear Mollye Collection. Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. jhsdelaware.org/collections/digital/items/show/200.

Steelman Family Photographs. 1939-1944. Courtesy of Cyd Steelman.

The Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association of Wilmington, Delaware. The Y Recorder. Jewish Historical Society of Delaware.

Secondary Sources

Balick, Marvin S. The Letters of “Dear Molly” a.k.a Mollye Sklut a.k.a. A person Who Made a Difference. Wilmington: Jewish Historical Society of Delaware, 2003.

Balick, Marvin S. A Social History of the West Second Street Jewish Community- Wilmington, Delaware 1930-1940. Wilmington: Jewish Historical Society of Delaware, 1997.

“Benjamin Sidney Steelman.” Find a Grave. Accessed October 25, 2022. www.findagrave.com/memorial/62496390/benjamin-sidney-steelman.

“Benjamin Sidney Steelman.” National Cemetery Administration. Accessed October 24, 2022. gravelocator.cem.va.gov/ngl/index.jsp.

Chapin, First Lieutenant John C. The 4th Marine Division World War II. Washington D.C.: U.S. Marine Corps History and Museums Division Headquarters, 1976. Accessed May 18, 2022. www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/The%204th%20Marine%20Division%20in%20World%20War%20II%20%20PCN%2019000412800.pdf.

Chapin, Captain John C. “Breaching the Marianas: The Battle for Saipan.” Marines in World War II Commemorative Series, National Park Service. Accessed May 18, 2022. www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/npswapa/extcontent/usmc/pcn-190-003123-00/sec1a.htm.

“The Fighting Fourth of WWII.” Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed May 18, 2022. www.vietnamproject.ttu.edu/dd786/fourth.html.

“Historical Perspective.” Fort Miles Historical Society. Accessed May 18, 2022. fortmilesha.org/historical-perspective/.

List of Wilmington High School Graduates Who Were Killed In World War II. Unpublished typescript, Wilmington High School, Wilmington, Delaware.

“Manhattan Project Spotlight: E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company.” Atomic Heritage Foundation. Last modified September 30, 2014. Accessed May 18, 2022. www.atomicheritage.org/article/manhattan-project-spotlight-ei-du-pont-de-nemours-company.

Morgan, Col. D. A., et al. History of the 4th Marine Division 1943-2000. 2000. www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/History%20of%20the%204th%20Marine%20Division%201943-2000%20%20PCN%2019000306300_1.pdf.

“PhM3c Benjamin Sidney Steelman.” Find a Grave. Accessed October 25, 2022. www.findagrave.com/memorial/3793259/benjamin-sidney-steelman.

“Tinian Island.” Atomic Heritage Foundation. Accessed September 7, 2022. www.atomicheritage.org/location/tinian-island.

Weissman, Cyd. “The Legacy of My Uncle’s Name.” Ritualwell. September 7, 2022. ritualwell.org/blog/the-legacy-of-my-uncles-name/?type=All.

World War II in Delaware. Wilmington: Delaware Historical Society, 2020. dehistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/WWII-in-DE-packet.pdf.