Private First Class Emory Alexander Brown

- Unit: 583rd Signal Aircraft Warning Battalion, Company A

- Service Number: 34456912

- Date of Birth: November 15, 1908

- Entered the Military: October 13, 1942

- Date of Death: September 9, 1944

- Hometown: Roxboro, North Carolina

- Place of Death: near Townsville, Queensland, Australia

- Cemetery: Section C, Grave 166. National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, Honolulu, Hawai'i

Mentored by Mrs. Amy Bradsher

Oak Tree Academy

2021–2022

Early Life

Sometimes heroes come from farms and factories, those who keep American life running smoothly—until they have to fight for that right with their very lives.

The life of this hero, Emory Alexander Brown, began on November 15, 1908. Samuel Pearly Brown (1881–1971) and Mary Emma Payne Brown (1889–1956) gave their son the names of his grandfathers, foreshadowing the importance that family would have in his life.

Brown spent his childhood on the family farm in Charlotte County, Virginia, becoming the oldest brother to six siblings: William Francis “Frank,” Elsie, Margaret, Ethel, Sherley, and Burrel. His education extended through grammar school (seventh grade).

Work

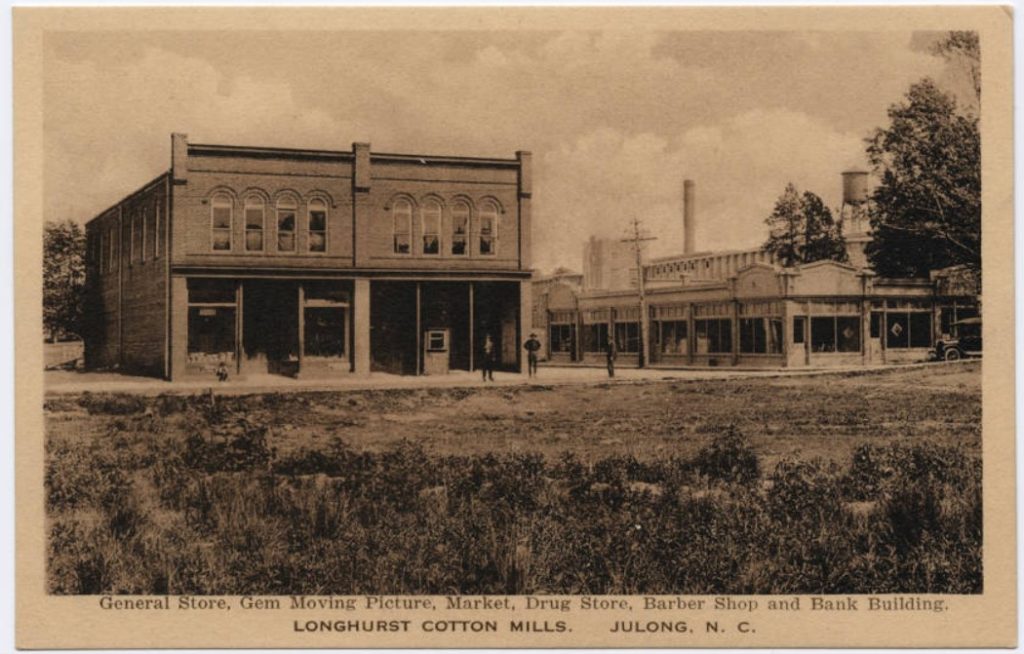

During the Great Depression, Brown moved to Person County, North Carolina, as a young adult, where he took a job at the Longhurst Cotton Mill as a frame operator. Here, he kept the machinery that transferred spun yarn onto spools running smoothly. The Jalong mill village, named after the plant’s founder, featured a largely self-sufficient community. Company money gave Brown access to the housing, movie theater, and general store.

Marriage

On April 5, 1930, the 21-year-old married a fellow mill worker in Halifax County, Virginia. Nancy Elizabeth Carver worked as a spinner at the Longhurst plant. Age 15 at the time of their union, Carver added six years to her age in the official documentation to become Brown’s wife.

The couple would not have children, but Brown’s family joined him in Person County by 1935. While his parents and youngest brother Burrel returned to Virginia before 1940, his three sisters married local men and remained in the area.

Homefront

Even before the United States’ entered World War II, the Person County Times encouraged readers to purchase defense bonds. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, residents leapt into action.

Person County citizens understood the importance of supporting the war effort and acted on it. Several war bond drives generated thousands of dollars of financial backing. Volunteer sewing and knitting groups crafted sweaters and other handmade items for soldiers. Rationing systems allowed everyone, regardless of their socioeconomic status, to contribute by reserving much-needed food and machinery for the military. Plans for a U.S. Army training camp in the county came close to construction. From money to morale, Personians successfully kept the cause alive.

With the increased community activity also came significant growth for Person County and its government seat, Roxboro. While the tobacco and food-growing industries stayed strong, the economy experienced a shift of focus from agriculture to manufacturing. Local businesses received a boost from wartime production.

Likewise, World War II played a major part in modernizing North Carolina. The state served as a top producer of ships and lumber for the military and ranked as the top provider of textiles in the nation.

With textile factories throughout the county, Personians helped the state achieve this title. Several companies added military supplies, such as parachutes, to their usual production. It is possible that the Longhurst Cotton Mill adjusted to meet wartime needs. If so, Brown would have taken part in these adjustments.

Military Experience

The Selective Training and Service Act passed in September 1940, marking the nation’s first peacetime draft. Brown registered soon after at age 31. A year later, on October 13, 1942, he joined the ten million men selected to serve their country during World War II.

The Lucky Company

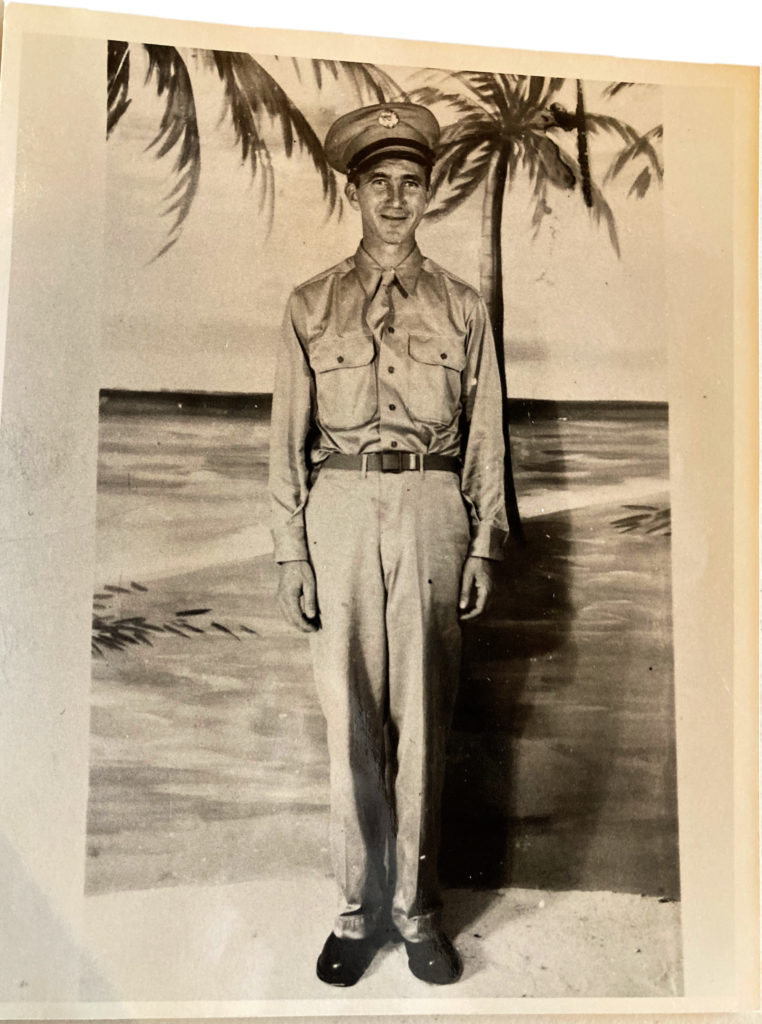

Brown’s military journey began with enlistment into the U.S. Army Signal Corps at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, followed by training at Drew Army Airfield in Tampa, Florida. This site specialized in preparing bomber crews and radarmen for duty. It is the birthplace of units like the 710th Signal Aircraft Warning Company, to which Brown was assigned as a private.

The 710th shipped out for the Pacific Theater in April 1943. That autumn, it became Company A of the 583rd Signal Aircraft Warning Battalion, Brown’s home for the remainder of his service. He would later write, “We have the name of being a lucky company and I sure hope our luck holds out and most of us can get back.”

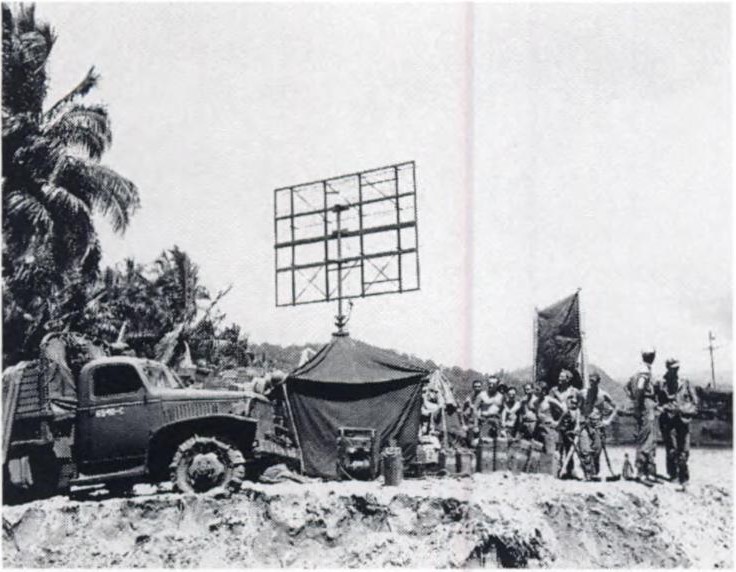

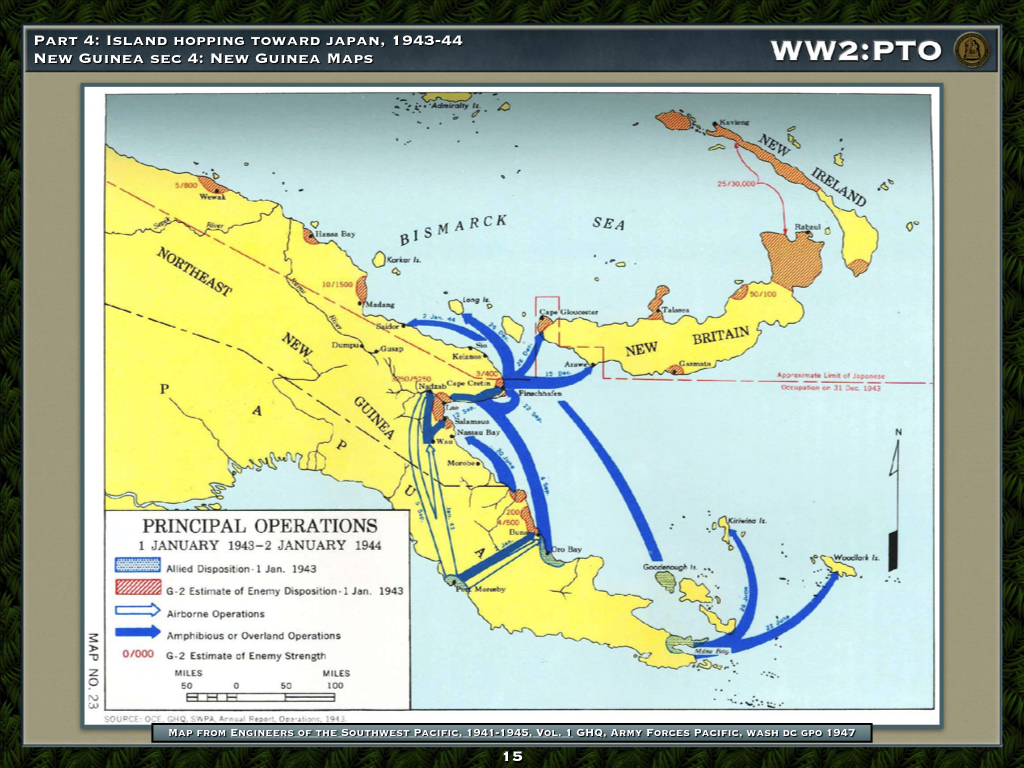

As part of the 583rd, Brown worked with advanced radar equipment to identify incoming enemy air raids and warn the connected airfields and aviators. The early knowledge of Japanese aerial movements protected the U.S. position and gave the air forces the advantage of time and intelligence. While signal air warning work is often overshadowed by the more dramatic stories of the war, it was the vigilance of soldiers like Brown who enabled significant offensive strategies to be completed more safely and effectively.

Brown and the 583rd advanced with the Allied front line along the northern coast of New Guinea. The campaign to wrest the island from Japanese control began in January 1942 and took two years. American soldiers endured disease, high temperatures, low food supplies, fierce battles, and harsh terrain; however, their efforts were not in vain. The liberation of New Guinea served as a gateway to the Philippines and forced the Japanese to divide their resources across the Pacific Theater.

Fighting for Peace, Dreams, and Family

Despite the reality of war he faced daily, Private Brown chose positivity. “I am getting on pretty good for this climate,” he said, one year into his service. He found reasons to laugh while joking around with the fighter pilots. He remembered his hobbies of hunting and trapping by observing the local game.

By March 1944, Brown was promoted to private first class. He stayed busy with the radar missions, and letters kept him connected to his family and happenings at home. Through words and pictures, Brown stayed close to his brother Frank and watched his young nieces grow up. Little Barbara (“Bobbie”) and Shirley Brown wrote their own letters to “Uncle Emory.”

In his replies, Brown shared his hopes for the future after the war. “I want to buy me a small farm or filling station when I get back . . . and you know I will trap in the winter.” He sent gifts to his family, including money and seashells. He expressed his desire to be with them again, saying, “I would sure like to see all of you now . . . maybe it won’t be as long as it has been before it is over.”

His letter on August 29, 1944, took on a more defined tone of hope. “The news sound[s] pretty good over on the other front. Maby [sic] it won’t be long before it is over over there . . . Tell Frank not to catch all the minks this season—for I don’t guess I can get back to help him this time but would sure like to.”

Though he missed his family, Brown embraced his duty by saying, “We have to go on before we come home.” He ended that letter with his usual heartfelt closing: “As ever, with love to all, your brother, Emory A. Brown.”

Eulogy

When the opportunity to take leave to Queensland, Australia, arose in August 1944, Brown accepted it. He had explained in his last letter, “I am leaving in the morning. I wasn’t going to take one [a leave] over here but I would like to see how civilians live, for I haven’t seen anything but jungles for over a year.”

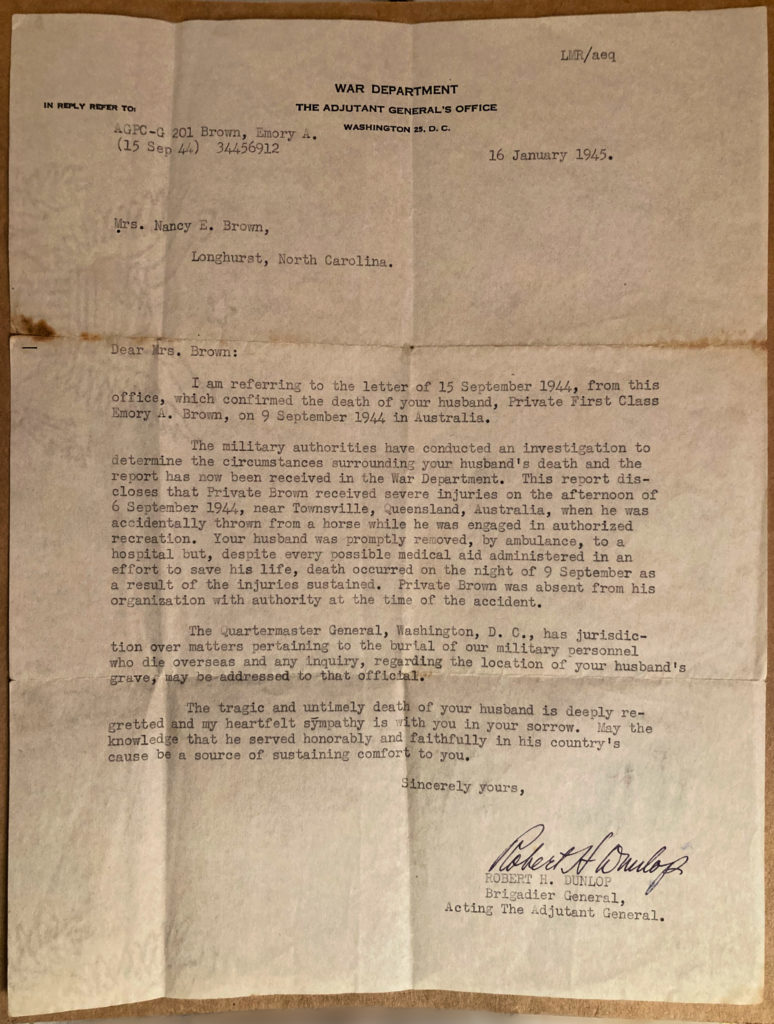

On Wednesday, September 6, he mounted a horse for an afternoon excursion, but an accident changed everything. At some point during his ride, the horse threw him and he fell, sustaining severe injuries.

An ambulance transported him to a hospital, where “every possible medical aid [was] administered in an effort to save his life.” Brown died on September 9, 1944.

His body was initially buried in the Ipswich United States Armed Forces Cemetery in Brisbane, Australia. He was reinterred into the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific on January 27, 1949, and lies there today.

A Hero’s Legacy

Private First Class Emory Alexander Brown is one of over 9,000 North Carolinians and over 60 Personians who did not return home, and among millions of Americans who sacrificed their comfort, community, and dreams to protect America’s freedom during World War II.

Brown’s name is etched in several memorials in Roxboro, North Carolina, but his story is much more than the words of his name. He is a hero whose service proves that from the quiet farmlands of central Virginia to the war-plagued jungles of New Guinea, courage can be found anywhere. He is a hero who leaves a legacy of love for his family and his country to follow.

Brown’s chapter may have ended in 1944, but America’s story—our story—continues because of heroes like him.

Reflection

Everything about the Sacrifice for Freedom®: World War II in the Pacific Student & Teacher Institute is carefully planned to have the maximum educational and inspirational impact on its participants. I am blessed and honored to have been involved this year—and I am not the same person as when I started.

The creative modules, readings, and assignments gave me a more accurate, balanced understanding of the war that will inform my dream careers in writing and public history education. Throughout the process, my analytical, critical thinking, research, and writing skills have been greatly strengthened and I look forward to further practicing them in the history field and beyond.

With the foundation I received from the pre-Hawaiʻi work, the in-person experiences were even more impactful. Exploring the sites, with their beauty and whispers of the past, filled my mind and heart. Our local guides set an example of bold passion for keeping history alive that I want to follow throughout my life. Interacting with the Hawaiian culture made the trip wonderfully unique, inspiring me to carry the true aloha spirit into my own community. The opportunity to unite with fifteen student peers of diverse backgrounds through our common love of history is one of many aspects of our trip that I will treasure.

I am still pondering all that the Silent Hero process has meant to me, but I know that it has affected me profoundly. I am constantly awed by the opportunity to honor a man who made such sacrifices through his service. No other academic project that I have participated in has had the same significance to me as bringing the story behind Private First Class Emory Brown’s name to life. The entire experience proved to me without a shadow of a doubt that history matters. Studying the past can absolutely impact the future; it has for me. Uncovering Private First Class Brown’s life has convicted me to live mine in a way worthy of his sacrifice and inspired me to do my part in protecting our freedom. It has further deepened my passion for studying and sharing history in a personal way and recognizing how ordinary people like me have made a difference. Between the skills that were sharpened through this program and the renewed passion I have for the past, I have never been more excited to discover more hidden heroes and tell their stories.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

“3249 Register In County For Draft.” Person County Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], October 17, 1940. North Carolina Newspapers. newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn96086016/1940-10-17/ed-1/seq-1/.

“Brief History of Roxboro Cotton Mills.” Person County Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], August 8, 1935.

Brown, Emory A. to Frank Brown. October 19, 1943. Courtesy of Shirley B. Dudley.

Brown, Emory A. to Mary Brown. March 24, 1944. Courtesy of Shirley B. Dudley.

Brown, Emory A. to Mary Brown. July 29, 1944. Courtesy of Shirley B. Dudley.

Brown, Emory A. to Mary Brown. August 29, 1944. Courtesy of Shirley B. Dudley.

Brown, Emory A. to Mrs. E. B. Payne. 1944. Courtesy of Shirley B. Dudley.

Brown Family Photographs. 1910–1942. Courtesy of Shirley B. Dudley.

“Buy Your War Bonds In Roxboro.” Person County Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], September 16, 1943. North Carolina Newspapers. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn96086016/1943-09-16/ed-1/seq-13/.

“Cottons In The War.” Person County Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], May 20, 1943. North Carolina Newspapers. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn96086016/1943-05-20/ed-1/seq-7/.

Delano, Jack. Rainy day on the main street of Roxboro, North Carolina. Photograph. May 1940. Library of Congress (2017747542). https://www.loc.gov/item/2017747542/.

Dudley, Shirley B. Telephone interview by author. March 25, 2022.

Dudley, Shirley B., Linda Hamlett, and Gretchen Brown. Interview by the author. June 10, 2022.

Dunlop, Robert H. to Nancy E. Brown. January 16, 1945. Courtesy of Shirley B. Dudley.

D.W. Oakley Studio. Longhurst Cotton Mill, Julong, N.C. Postcard. Durwood Barbour Collection of North Carolina Postcards, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, University of Norh Carolina, Chapel Hill (P077;4-384). https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/nc_post/id/3341.

“Emory A. Brown.” National Cemetery Administration. Accessed February 18, 2022. https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov.

Emory A. Brown. Internment Record, March 21, 1949. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

Emory A. Brown. World War I, World War II, and Korean War Casualty Listings. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

Emory A. Brown; World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946. https://ancestry.com.

Emory A. Brown. World War II Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

Emory Alexandria Brown. World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

Holliday Studio. Longhurst Cotton Mills, Roxboro, N.C. Postcard. Durwood Barbour Collection of North Carolina Postcards, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (P077;9-396). https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/nc_post/id/3571.

“Japan Surrenders.” The Courier=Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], August 16, 1945. North Carolina Newspapers. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92061512/1945-08-16/ed-1/seq-1/.

“Knitters Urged to Up Sweater Quota.” The Courier=Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], January 18, 1945. North Carolina Newspapers. newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92061512/1945-08-16/ed-1/seq-1/.

“Long Was Pioneer In Roxboro’s Industrial Life.” The Roxboro Courier, Sesquicentennial Edition, 1941.

“Many Get Gold Star Certificates.” The Courier=Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], August 6, 1945.

Marriage License, Emory Alexander Brown and Nancy Elizabeth Carver. April 5, 1930. Halifax County Courthouse.

Mixer, Eldon Loraine. Interview with Eldon Loraine Mixer. Video file, May 27, 2015. Veterans History Project, Library of Congress (AFC/2001/001/99802). https://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp/story/loc.natlib.afc2001001.99802/mv0001001.stream.

Merritt, John W. Picturing Historic Person County. Compiled by Eddie Talbert and Edith Grey. Charleston: The History Press, 2007.

Murta, Frank B. Interview with Frank B. Murta, Part 1 of 2. January 1-2, 2008. Veterans History Project, Library of Congress (AFC/2001/001/67690). https://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp/story/loc.natlib.afc2001001.67690/mv0001001.stream.

Murta, Frank B. Interview with Frank B. Murta, Part 1 of 2. January 1-2, 2008. Veterans History Project, Library of Congress (AFC/2001/001/67690). https://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp/story/loc.natlib.afc2001001.67690/mv0002001.stream.

Nancy Elizabeth Carver. North Carolina State Bureau of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Certificate of Birth. July 4, 1914. Person County Register of Deeds.

Newell, Jean Davis. Interview by author. March 25, 2022.

Newell, Jean Davis. Interview by Caitlin R. Donnelly, Person County Museum of History Oral History Project. Summer 2006.

North Carolina. Person County. 1910 U.S. Census. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

North Carolina. Person County. 1920 U.S. Census. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

North Carolina. Person County. 1930 U.S. Census. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

North Carolina. Person County. 1940 U.S. Census. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

“Our Record Is At Stake.” The Courier=Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], June 18, 1945. North Carolina Newspapers. newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92061512/1945-06-18/ed-1/seq-6/.

“Pfc. E. A. Brown Reported Dead.” The Courier=Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], September 21, 1944.

“Reported Dead.” The Courier=Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], October 2, 1944.

“Roxboro Industrial Plants Continue Full Operations.” The Courier=Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], August 23, 1945. North Carolina Newspapers. newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92061512/1945-08-23/ed-1/seq-1/.

“Roxboro To Go On War Basis.” Person County Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], December 11, 1941. North Carolina Newspapers. newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn96086016/1941-12-11/ed-1/seq-1/.

Virginia. Charlotte County. 1910 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Virginia. Charlotte County. 1920 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Virginia. Charlotte County. 1930 U.S. Census. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

“War Effort Forms Vital Part Of Present Day Life In City.” Person County Times [Roxboro, North Carolina], July 8, 1943. North Carolina Newspapers. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn96086016/1943-07-08/ed-1/seq-9/.

Secondary Sources

“583rd Signal Aircraft Warning Battalion.” Mobile Radar. Accessed May 11, 2022. http://www.mobileradar.org/army_units_562_599.html#ar_583.

“583rd Signal Aircraft Warning Battalion: Company A.” Mobile Radar. Accessed May 11, 2022. www.mobileradar.org/Documents/583rd/583rd_co_a.html.

“710th Signal Aircraft Warning Company.” Mobile Radar. Accessed May 11, 2022. http://www.mobileradar.org/army_units_600_2691.html#ar_710.

Billinger, Robert D., Jr. and Jo Ann Williford. “World War II, Part 1: Introduction.” NCpedia, State Library of North Carolina. Last modified 2006. Accessed April 20, 2022. www.ncpedia.org/world-war-ii-part-2-north-carolina.

Billinger, Robert D., Jr. and Jo Ann Williford. “World War II, Part 2: North Carolina Contributions in Battle and on the Home Front.” NCpedia, State Library of North Carolina. Last modified 2006. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.ncpedia.org/world-war-ii-part-2-north-carolina.

Brown, Louis. Technical and Military Imperatives: A Radar History of World War II. New York: Taylor & Francis, 1999.

Brown, Marvin A. and James R. Snodgrass. An Historic Architectural Survey of US 501 from NC 49 in Roxboro to the Virginia State Line. Raleigh: Greiner, Inc., 1995. https://files.nc.gov/ncdcr/historic-preservation-office/PDFs/ER_93-7903.pdf.

Drea, Edward J. New Guinea. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 2019. https://history.army.mil/html/books/072/72-9/index.html.

“Drew Army Airfield.” Museum of Florida History. Accessed May 25, 2022. www.museumoffloridahistory.com/exhibits/permanent-exhibits/world-war-ii/historical-sites/westcentral-listing/drew-army-airfield/.

Eisel, Braxton. “Signal Aircraft Warning Battalions in the Southwest Pacific in World War II.” Air Power History, Fall 2004, 14-23. www.jstor.org/stable/26274571.

Guise, Kimberly. “Mail Call: V-mail.” The National WWII Museum New Orleans. Last modified December 7, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2022. www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/mail-call-v-mail.

Kreis, John F. “Part Two: World War II.” In Air Warfare and Air Base Defense 1914-1973, 53-261. Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History, 1988. media.defense.gov/2010/Sep/22/2001330044/-1/-1/0/AFD-100922-032.pdf.

Leloudis, James and Kathryn Walbert. “Work in a Textile Mill.” Anchor, State Library of North Carolina. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/work-textile-mill.

Lengel, Ed. “Angel and Victims: The People of New Guinea in World War II.” The National WWII Museum New Orleans. Last modified August 9, 2020. Accessed May 31, 2022. www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/people-of-papua-new-guinea.

“Manson Park.” City of Ipswich. Accessed August 18, 2022. https://www.ipswich.qld.gov.au/services/searches-and-enquiries/cemeteries/cemeteries-in-ipswich/manson_park.

“Manson Park Burials Register.” City of Ipswich. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://www.ipswich.qld.gov.au/services/searches-and-enquiries/cemeteries/cemeteries-in-ipswich/manson_park/burials_register.

“New Guinea Campaign.” U.S. Army Center of Military History. Accessed June 20, 2022. history.army.mil/html/bookshelves/resmat/wwii/part04PTO/new_guinea/sec01.html.

Newell, David B., Sr. Tour of Longhurst Cotton Mill. Roxboro, North Carolina. April 28, 2022.

North Carolina’s WWII Experience. Directed by Scott H. Davis. 2016. PBS North Carolina. Accessed April 20, 2022. www.pbs.org/video/unc-tv-presents-north-carolinas-wwii-experience/.

“The Pacific Strategy, 1941-1944.” The National WWII Museum. Accessed April 28, 2022. www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/pacific-strategy-1941-1944.

“Research Starters: The Draft and World War II.” The National WWII Museum. Accessed April 26, 2022. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/students-teachers/student-resources/research-starters/draft-and-wwii.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The United States Army Signal Corps.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. Accessed May 31, 2022. encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-united-states-army-signal-corps.

“World War II – Asiatic-Pacific Theater Campaigns.” U.S. Army Center for Military History. Accessed April 28, 2022. history.army.mil/html/reference/army_flag/ww2_ap.html.