Private George Ernest Pearce

- Unit: 2nd Battalion, 161st Depot Brigade; transferred to Miscellaneous Division Quartermaster Corps

- Date of Birth: June 20, 1895

- Entered the Military: May 5, 1917

- Date of Death: June 12, 1946

- Hometown: San Diego, California

- Cemetery: Section A, Site 143-A. Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery, San Diego, California

Frances Parker School

2017–2018

Before the War

Like so many World War I soldiers, George Ernest Pearce was an immigrant. He was born in Portsmouth, England, on June 20, 1895, to parents Henry George and Elizabeth Mary (Plater) Pearce. Pearce’s father died before he was three years old, so his mother worked as a dressmaker to support Pearce and his younger brother, Jack.

George and Jack were influenced by their uncle, Alfred. Alfred left England when George was a boy, and returned regularly to describe life in North America. Alfred first emigrated to Cookstown, near Ontario, Canada, to try his hand at farming. In 1913, as the age of 18, George booked passage to Canada on the ship Alaunia, signing himself as a “farm laborer” on the ship’s register. His brother, Jack, emigrated to Canada the same year and married there in 1915.

Shortly thereafter, Uncle Alfred moved to Salt Lake City to run a grocery; again, George followed his uncle. In 1916, George applied to be a U.S. citizen, filing a Declaration of Intention. When President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany in April, 1917, George Pearce was working as a cashier in the music shop next to his Uncle Alfred’s grocery in central Salt Lake City, Utah.

Military Experience

Supporting the U.S. Army: Pearce in the Quartermaster Corps

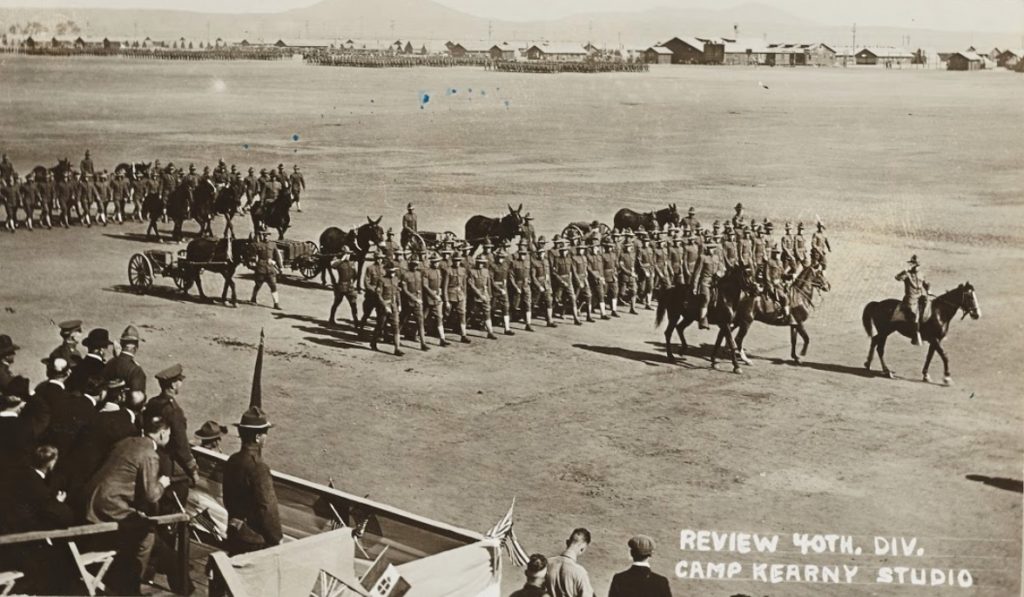

Pearce enlisted in the U.S. Army in early May 1917. He was initially sent to Fort Douglas, a camp just east of Salt Lake City where he was placed in the 21st Division, Company C. Almost immediately, the 21st Division transferred to Camp Kearny, San Diego, and reorganized into the 31st Infantry Brigade. During the move, Private Pearce was reassigned to the Quartermaster Corps.

During the first few months of the war, the U.S. Army needed military personnel to work in the Quartermaster Corps, the supply division that handled transportation, construction, food service, and distribution. The Quartermaster Corps was not allowed to recruit soldiers expressly for these positions, so they re-assigned soldiers who had already enlisted. They grouped recruits according to experience and profession, including cooks, bakers, butchers, auto mechanics, plumbers, carpenters, firefighters, typewriters, and clerks. Perhaps because he had worked as a cashier before he enlisted, Pearce was reassigned in September 1917 to the Quartermaster Corps in Camp Kearny to serve as a clerk.

Camp Kearny, located 11 miles north of San Diego on 12,721 acres, had been purchased by the federal government in May 1917. It was one of 32 new camps created in 1917 to house and train 40,000 recruits. The Quartermasters organized the system of roads, the placement of tents and construction of barracks, a hospital, mess halls, sewage, and headquarters buildings. In addition, they built stables and provided provisions for the horses that would be used for training recruits. Some of these horses would eventually be shipped to France to serve the American Expeditionary Forces. As a clerk, Private Pearce would have overseen payments to and from these supply groups. He worked as a clerk from September to December 1917.

Private Pearce was honorably discharged from the Army on December 6, 1917, due to a physical disability. Since his work as a clerk was not arduous, it is likely that at this time the camp physician discovered his heart condition. For the rest of his life, Private Pearce suffered from heart trouble and bouts of weakness; his daughter remembers that on his days off he always slept during the afternoons. Pearce’s discharge notice indicates that he had provided “honest and faithful” service in the Quartermaster’s Corps. The notice affirms that he was never absent without leave and he had no infractions. After six months of service, Private Pearce became a veteran of World War I.

Veteran Experience

A Life in Banking

Although his service in the U.S. Army was short, the experience shaped the remainder of Pearce’s life. In 1920, he became a citizen of the United States. Recognizing that 18% of the U.S. Army were immigrants, Congress passed legislation that sped up the naturalization of foreign-born veterans. Pearce was naturalized in just under four years.

In addition, Pearce found his vocation while in the Army. From the time he was discharged, he worked in accounting and banking in San Diego. He first worked at the Bank of Italy as an assistant controller, performing duties related to payroll. When the bank was purchased by Southern Trust and Commerce Bank, he became an auditor in that organization. At Southern Trust and Commerce that he met his future wife, Elizabeth “Betty” Alice Williams, who worked as a cashier. The couple married in 1922. In 1920, Pearce’s Uncle Alfred came out to San Diego to work as a chiropractor. Pearce’s brother, Jack, moved to San Diego as well, and it is likely that his brother George helped him land his job driving armored cars for the bank.

By 1926, Pearce and his wife had purchased their home on 32nd Street and started a family. Virginia, “Ginger” to her father, was born in 1925 and her sister, Betty Mae, was born four years later. An entry in the 1926 San Diego directory shows Pearce’s name in bold type, one of only three bolded names on the page.

Virginia remembers her father as a serious man, who worked hard to keep his family afloat during the Great Depression. He was dedicated to his profession. One of the pieces of memorabilia that Pearce saved in an album was an article he wrote entitled “What Do you Know About Your Bank?” In the same album, he saved a poem that reflected his belief in hard work:

“Bite off more than you can chew, then chew it.

Plan for more than you can do, then do it.

Hitch your wagon to a star, keep your seat, and there you are.”

—Unknown

Pearce sang hymns and could draw. He saved two of his cartoons in the album. He also included a photograph of little Ginger, with an article about how a sleeping child reflects the image of the Divine. The only document he saved from the war was a notice about his reassignment as a clerk in the Quartermaster Corps.

George Pearce died of heart failure in 1946 at the age of 51 after an allergic reaction to aspirin. He was buried in Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery, a military cemetery in San Diego.

Commemoration

George Ernest Pearce served his adopted country in the Quartermaster Corps in World War I. His service in the war was a snapshot of his later life. He gave “honest and faithful service,” working hard for his employers and his family during lean years. He lived a quiet and successful life. He was survived by his wife, Betty, who lived until 1993, and his two daughters. His daughter, Virginia, still remembers “Daddy” fondly.

Bibliography

16th Division; Records of the American Expeditionary Forces (World War I), Records of Combat Divisions, 1918–1919, Record Group 120 (Boxes 1–4); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

“A Brief History of Fort Douglas.” Historic Fort Douglas at the University of Utah. Accessed July 15, 2018. http://web.utah.edu/facilities/fd/history/history.html.

California. San Diego County. 1920 U.S. Census. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

California. San Diego County. 1930 U.S. Census. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

California. San Diego County. 1940 U.S. Census. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

Canadian Passenger Lists, 1865–1935. Library and Archives Canada Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

England & Wales, Civil Registration Birth Index, 1837–1915. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

Garamone, Jim. “World War I: Building the American Military.” Department of Defense. Last modified March 29, 2017. Accessed August 25, 2018. https://www.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/1134509/world-war-i-building-the-american-military/.

George Ernest Pearce Pay Voucher; World War I Enlisted Men Final Military Pay Vouchers, 1917-1921, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration, 1789-2007, Record Group 64; National Archives and Records Administration — St. Louis.

George Pearce. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850–2010. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

Inter Film Service. California Mobilization Camp almost ready.… Photograph. May 27, 1918. National Archives and Records Administration (165-WW525D9-au). Image.

Inter Film Services. Scenes at Camp Kearny, Linda Vista, Cal. Photograph. May 27, 1918. National Archives and Records Administration (165-WW525D22-au). Image.

Manifests of Alien Arrivals at Port Huron, Michigan, February 1902–December 1954; Record Group: 85, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

Martin, John. “Patriotism and Profit: San Diego’s Camp Kearny.” Journal of San Diego History 58, no. 4 (2017): 247–272.

Naturalization Records in the Superior Court of San Diego, California, 1883–1958; Microfilm Roll: 6; Microfilm Serial: M1613. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, D.C. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

Pearce Family Photographs. 1905–1940. Courtesy of Pearce Family.

Review of Fortieth Division, U.S.A. Camp Kearny, Calif.… Photograph. 1918. National Archives and Records Administration (165-WW89A45-au). Image.

Sharpe, Maj. Gen. Henry G. The Quartermaster Corps in the Year 1917 in the World War. New York: Century Co., 1921.

State Capitol Construction 16 May 1914. Photograph. May 16, 1914. Utah State Historical Society.

“The Immigrant Army: Immigrant Service Members in World War I.” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Last modified July 14, 2017. Accessed August 25, 2018. https://www.uscis.gov/history-and-genealogy/our-history/immigrant-army-immigrant-service-members-world-war-i.

“U.S. Grant and Am. Natl Bank Building.” Postcard. 1897. New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-9fcb-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.