First Lieutenant George Ham Cannon

- Unit: Fleet Marine Force, 6th Defense Battalion, Battery H

- Service Number: O-005837

- Date of Birth: November 5, 1915

- Entered the Military: July 5, 1938

- Date of Death: December 7, 1941

- Hometown: Detroit, Michigan

- Place of Death: Midway Island

- Award(s): Congressional Medal of Honor, Purple Heart, American Defense Service Medal with Base Clasps

- Cemetery: Section C, Grave 1644. National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, Honolulu, Hawaiʻi

Mentored by Mrs. Tara Fugate

Fraser High School

2021–2022

Early Life

First Lieutenant George Ham Cannon—affectionately known as Hammy to his close friends and family–was the second child born to Benjamin and Estelle Cannon on November 5, 1915, in Webster Groves, Missouri.

Two years before the United States entered World War I, the Cannons moved to Detroit, Michigan, a booming blue-collar city that became known as the Arsenal of Democracy. As a student at Southeastern High School, Cannon was involved in campus life. He participated in the school’s band, string ensemble, and orchestra, and was a member of the school’s chess club, magic club, and House Council. As his senior year approached, Cannon began looking into post-secondary options.

Though it was his dream to attend the University of Michigan, Cannon’s love of country and desire to carry on the family tradition of military service led him to enroll at Culver Military Academy in Marshall County, Indiana. He stayed at Culver until 1935 when he was accepted at the University of Michigan to study mechanical engineering.

At the University of Michigan, Cannon continued to thrive. He joined the Sigma Chi Fraternity as well as the band, choral union, orchestra, and Varsity glee club. Throughout his time at the University of Michigan, he was also a member of Scabbard and Blade, an organization similar to the Reserves Officers Training Corps (ROTC).

In June 1938, Cannon completed his Bachelor of Science degree and graduated with honors.It was around this time that his military career began. In his senior year, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Engineer Reserve. However, upon graduation from the University of Michigan, he received a two-year scholarship to attend the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

Date: c. 1920

Homefront

First Lieutenant Cannon lived in Ann Arbor, Michigan in the years leading up to the war. Just before the war, the Detroit Historical Society described the city at the beginning of “boom years for development,” while Ann Arbor was a quiet town, largely made up of university students. The war accelerated Detroit’s boom and transformed Ann Arbor into an industrial city.

As the Encyclopedia of Detroit explains, Detroit became known as The Arsenal of Democracy because “it is generally agreed that no American city contributed more to the Allied Powers during World War II.” Manufacturing was key to this contribution.

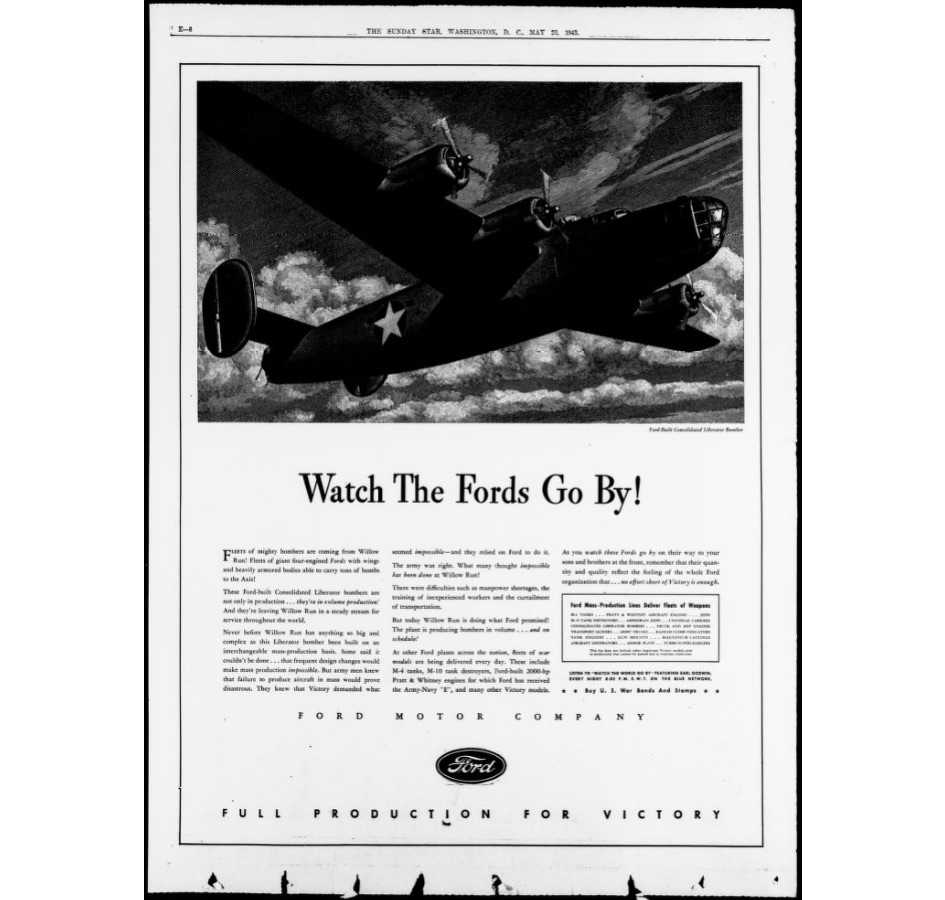

As war raged in Europe, Henry Ford opened a plant at Willow Run in Washtenaw County. Much like his Detroit plants, the plant quickly began manufacturing weapons of war, completing its first airplane parts the day after Pearl Harbor was bombed. Willow Run’s first complete bomber was finished in December 1941. Throughout the war, Ford continued to manufacture B-24 bombers, aircraft essential to the Allied victory. By March 1944, Willow Run alone could produce one complete bomber every 63 minutes.

As a result, unemployment basically disappeared. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, roughly 350,000 workers flocked to Detroit and its surrounding cities to find work in the plants and contribute to the war effort.

Ann Arbor made an effort to curb food shortages by creating Victory Gardens; even the University of Michigan added vegetable patches maintained by university staff. Similarly, the Women’s Land Army was formed to increase food production. One University of Michigan student and WLA member explained, “…my fiance was killed in this war and I feel that I, by helping to produce food so vitally needed by our soldiers, can in part, make up for the loss of at least one fighting man.”

Even children participated in the war effort, collecting milkweed for flotation devices and the Boy Scouts ran a paper drive.

Walter Reuther, the President of the United Auto Workers, summarized the Detroit area’s efforts best when he said, “Like England’s battles were won on the playing fields of Eton, America’s were won on the assembly lines of Detroit.”

Military Experience

After graduation, Cannon officially resigned from the U.S. Army and accepted the scholarship offered to him by the U.S. Marine Corps. On July 5, 1938, he was ordered to report for duty at the Philadelphia Navy Yard where he served as a second lieutenant. Once he completed basic training, he served as a Sea Marine until 1941.

These were the first stepping stones to Midway Island.

On February 16, 1941, Cannon joined the 2nd Defense Battalion, Battery H, in San Diego, California. Then, in March, his battery joined the 6th Defense Battalion. In June 1941, he was promoted to first lieutenant.

One month later, his battalion set sail for Pearl Harbor, Hawaiʻi. However, he did not stay long. On September 7, 1941, exactly three months before the fateful attack, he reported for duty on Midway Island.

On Midway, First Lieutenant Cannon was a platoon leader and a member of the Defense Battalion Coding Board, working to decode Japanese messages.

On the night of December 7, 1941, the Japanese led a surprise attack on Midway Island. The attack lasted only 23 minutes, but it cost First Lieutenant Cannon his life.

The inadequate facilities at Midway could not withstand the Japanese attack, and despite doing their best to defend the base, the bombardment left four men killed in action and 19 wounded. When a Japanese artillery shell hit his bunker, mortally wounding Cannon, he made sure that all of his men got out and the radios were running before leaving his command.

At the age of 26, First Lieutenant Cannon went above and beyond the call of duty. According to the Marine Corps’ records, “. . . George Ham Cannon repeatedly refused medical attention and stayed at his post until the bombardment was over and no one else at the post was in danger.” Only minutes after arriving at an aid station, Cannon died from blood loss.

Date: November 24, 1941. U.S. Navy Photographer. Naval History and Heritage Command (80-G-451086).

Eulogy

When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt addressed the nation the day after the Japanese attacks, he called December 7, 1941, a day that would live in infamy, and it has. It was a day that changed America, pulling the United States out of isolation and into worldwide war. For many Americans December 7, 1941, was a call to duty, and to those brave Americans, the life of First Lieutenant George Ham Cannon served as an example. His short life and his service to his country was an example of leadership and bravery, of courage and patriotism, and personal sacrifice for the common good.

His heroic and selfless actions posthumously earned him the Congressional Medal of Honor. He was the first Marine to receive this high honor. Additionally, he was also posthumously awarded a Purple Heart, American Defense Service Medal with Base Clasps, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and a World War II Victory Medal.

Initially, First Lieutenant Cannon was buried at Halawa Cemetery in Honolulu; however, in 1947, his mother requested that he be moved to what is now his final resting place in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. To memorialize him at home, his family placed a cenotaph at Glen Cove Cemetery in Knightstown, Indiana, in the family’s plot. Then, in May 1943, a destroyer escort called the USS Cannon (DE-99) was commissioned and named in his honor.

Though First Lieutenant Cannon did not see past the first day of the war, his contribution and example will not be forgotten, and his memory and legacy live on in the service men and women who follow in his footsteps.

Reflection

In so many ways, participating in the Sacrifice for Freedom®: Student and Teacher Institute has broadened my horizons.

Going into the program, I thought I knew a lot about the Pacific Theater. It’s a topic I’ve always been interested in; however, with every topic we covered and every site we visited, I found myself learning new things, specifically about pre-war Japan; and that new knowledge made me think about the things I already knew in a new way.

I didn’t know that Japan had such a long and proud military history or that the start of World War II could be traced back to a Japanese conflict with China in Manchuria. Similarly, I hadn’t realized the Japanese had never been on the losing side of a war, that they didn’t even have a word for “surrender.” That knowledge really changed how I thought about the events that led up to the war’s end.

As I look back on the trip to Hawaiʻi, I am so grateful. I made new friends with people from all over the world—friends who share my love and appreciation for history and the stories of veterans, friends who shared such an amazing, once-in-a-lifetime experience. The places we all visited on this trip are places I never thought I would get to see in person. Seeing them in person far exceeded all expectations I had; but, as incredible as each site we visited, there were two that had a deep impact on me: the USS Arizona Memorial and the National Cemetery of the Pacific. I doubt I will ever forget the feeling I had when I looked down into the ocean where the men interred on the USS Arizona now rest or how moving it was to walk along the rows of graves of men who made the ultimate sacrifice, to see the final resting places of the many who will never have the chance to tell their own stories.

This experience reminded me of the importance of remembering and honoring the fallen, and the importance of helping them tell their stories so that their stories will not be lost.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

“Actual Production on Bombers at the Willow Run Plant.” Detroit Times [Detroit, Michigan], May 7, 1942. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88063294/1942-05-07/ed-1/seq-42/.

Cannon Family Photographs. 1920-1943. Courtesy of Samuel P. March.

“Brother Honored At Academies.” The South Bend Tribune [South Bend, Indiana], May 30, 2000. Newspapers.com (519542357).

“Destroyer Escort Vessel Hits Water at Dravo.” The News Journal [Wilmington, Delaware], May 26, 1943. Newspapers.com (161899900).

First Lieutenant George H. Cannon, USMC. Photograph. Naval History and Heritage Command (NH 105688). https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-people/c/cannon-george-h/nh-105688.html.

George H. Cannon. World War II and Korean Conflict Veterans Interred Overseas. https://www.ancestry.com/.

George Ham Cannon. Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl), 1941-2011. https://www.ancestry.com/.

George Ham Cannon. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962. Digital images. https://www.ancestry.com/.

George Ham Cannon. “Rosters of World War II Dead, 1939-1945.” https://www.ancestry.com/.

George Ham Cannon. Southeastern High School Yearbook. 1932. Digital images. https://www.ancestry.com/.

George Ham Cannon. University of Michigan Yearbook. 1938. Digital images. https://www.ancestry.com/.

Japanese attack on Midway Island, 7 December 1941. Photograph. Naval History and Heritage Command (80-G-2299). https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nara-series/80-g/80-G-00001/80-G-2299.html.

Liftoff, Judy Barrett and David C. Smith. “‘To the Rescue of the Crops.’” Prologue 25, no. 4 (Winter 1993). https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1993/winter/landarmy.html.

“Local Folk Attend Commencement in Michigan.” The Hancock Democrat [Greenfield, Indiana] Newspapers.com (95486807).

“Lt. George Ham Cannon Dies at Midway Island.” The Hancock Democrat [Greenfield, Indiana], January 15, 1942. Newspapers.com (102874714).

Michigan. Wayne County. 1930 U.S. Federal Census. https://www.ancestry.com/.

Michigan. Wayne County. 1940 U.S. Federal Census. https://www.ancestry.com/.

Missouri. St. Louis County. 1920 U.S. Federal Census. https://www.ancestry.com/.

Midway Island: November 1941. Photograph. Naval History and Heritage Command (80-G-451086). https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn/explore/photography/wwii/wwii-pacific/us-entry-into-wwii-japanese-offensive/1941-december-7-japanese-attack-midway-island/80-g-451086.html.

Rosener, Ann. Production. Willow Run bomber plant . . . Photograph. July 1942. Library of Congress (2017693362). https://www.loc.gov/item/2017693362/

“Watch the Fords Go By!. [Advertisement]” Evening Star [Washington, D.C.], May 23, 1943. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-05-23/ed-1/seq-64/.

Secondary Sources

“1LT George Ham Cannon.” Find a Grave. Accessed October 25, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/3771015/george-ham-cannon.

“Arsenal of Democracy.” Encyclopedia of Detroit, Detroit Historical Society. Accessed August 13, 2022. detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/arsenal-democracy.

Beigel, Bill. “Honoring Lt. George H. Cannon, USMC, on Medal of Honor Day.” Last updated November 17, 2018. Accessed October 25, 2022. www.ww2research.com/george-h-cannon-moh/.

“Cannon, George H.” Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed August 13, 2022. www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-people/c/cannon-george-h.html.

“Cannon, George Ham, 1stLt.” Together we served. Accessed August 13, 2022. marines.togetherweserved.com/usmc/servlet/tws.webapp.WebApp?cmd=ShadowBoxProfile&type=Person&ID=50112.

“First Lieutenant George Ham Cannon, USMC (Deceased).” Marine Corps University. Accessed August 13, 2022. www.usmcu.edu/Research/Marine-Corps-History-Division/Information-for-Units/Medal-of-Honor-Recipients-By-Unit/1stLt-George-Ham-Cannon/.

“George Ham Cannon.” Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Accessed August 13, 2022. www.cmohs.org/recipients/george-h-cannon.

“George Ham Cannon.” National Cemetery Administration. Accessed October 25, 2022. https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/ngl/index.jsp.

“Japanese attack on Midway Island.” Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn/explore/photography/wwii/wwii-pacific/us-entry-into-wwii-japanese-offensive/1941-december-7-japanese-attack-midway-island.html.

Taylor, Alan. “Detroit in the 1940s.” The Atlantic, January 14, 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2015/01/detroit-in-the-1940s/384523/.

“The War Hits Home.” Ann Arbor District Library. Accessed April 13, 2022. aadl.org/moaa/pictorial_history/1940-1974pg1.