Steward Third Class Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay

- Unit: USS Wahoo (SS-238)

- Service Number: 4210726

- Date of Birth: April 3, 1921

- Entered the Military: December 2, 1940

- Date of Death: October 11, 1943

- Hometown: Malesso’, Guam

- Place of Death: Soya/La Perouse Strait (between Sakhalin and Hokkaido, Japan)

- Award(s): Purple Heart

- Cemetery: Courts of the Missing. National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, Honolulu, Hawaiʻi

Mentored by Lazaro Quinata

Father Duenas Memorial School

2021–2022

Early Life

On April 3, 1921, Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay was born the eldest son of Juan Castro and Carmen Chargualaf Manalisay. Jesus was CHamoru, the Indigenous people of Guam, an island in the vast Pacific that the U.S. won control of in the Spanish-American War of 1898. He grew up in the village of Malesso’, at the southernmost end of the island, away from the harbor and Hagåtña, the capital.

Jesus attended the Merlyn G. Cook School in Malesso’, for four years. This was because the U.S. Navy, which governed Guam, made school compulsory from ages seven to twelve. A particular focus was placed on educating the children in English. As a result, Jesus was able to read, write, and speak English. The Merlyn G. Cook School also had a Parent Teacher Association and Christmas program.

Jesus Manalisay and his family were farmers, like most other residents of Guam, who used subsistence agriculture to provide their own food during this time. The 1940 census logged his occupation as a “farm laborer.” The Manalisay family also lived close to the ocean, so Jesus probably grew up fishing as well.

Many CHamorus joined the U.S. Navy around this period of history. However, due to racial segregation in the military, CHamoru soldiers could only typically be mess attendants or stewards. Despite this, many still joined, because it had a few perks. CHamorus who joined the Navy were sometimes called the “sindålun mantikiya,” or butter sailors. This is because soldiers gained access to shop in the military bases, where prices were almost always cheaper.

CHamoru mothers were probably extremely worried about their sons joining the U.S. Navy. Folk songs from the time period described the mothers’ emotions when their sons left.

Homefront

Hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, on December 8, 1941 (due to time zones), Manalisay’s home island of Guam was invaded by Japanese forces. This was also the date of an annual festival celebrating Santa Marian Kamalen, the patron saint of Guam, so many locals were attending mass when they first heard enemy aircraft flying overhead and dropping bombs. Japanese soldiers swiftly overpowered the small force defending the island; it was left deliberately undermanned due to being difficult to defend.

The Japanese occupation lasted for around two and a half years and was brutal. CHamorus were often forced to work for food, and in the later stages of the occupation, as American reclamation became imminent, the Japanese soldiers committed horrific atrocities on civilians. Many CHamorus carried with them the hope that the Americans would return, and in protest, sang the following song:

“Eighth of December, 1941,

People went crazy, right here in Guam

So Uncle Sam, Sam, my dear old Uncle Sam,

Won’t you please come back to Guam!”

Some of the atrocities took place in Manalisay’s village, Malesso’. On July 15, 1944, Japanese soldiers marched 30 prominent or rebellious villagers to a cave. The soldiers massacred the CHamorus with grenades, swords, and bayonets, but 14 managed to survive by hiding behind corpses. The next day, the Japanese killed 30 of the strongest, tallest men of Malesso’ in fear that they would be overpowered by them. They were correct to be feared, as days later, the people of Malesso’ rose up and killed most of the Japanese soldiers. This meant that Malesso’ was the only village on Guam to liberate itself.

Afterward, six men paddled out to sea to reach the U.S. Navy ships. One of these paddlers was Joaquin Chargualaf Manalisay, Jesus’s younger brother.

In the following battle that ensued, around 2,000 American soldiers and 1,000 civilians lost their lives in a bloody three-week campaign. The people of Guam will forever be grateful to them, and their sacrifices will never be forgotten.

After a hard-fought battle that lasted three weeks, Guam was liberated, thanks to the numerous sacrifices of the American soldiers and CHamorus. Annually, Liberation Day is celebrated with a parade on July 21, the day American service members arrived. Memorials commemorating the anniversaries of the Tinta and Faha massacres are also held. Guam will forever be grateful for all the courageous sacrifices made by American soldiers in liberating the island, and the massive hardships our ancestors had to endure during the war.

Military Experience

Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay enlisted in the U.S. Navy on December 2, 1940. His initial training began aboard the USS Robert L. Barnes in Apra Harbor, Guam. He was then sent to the U.S. mainland aboard the USS Chaumont in 1941. Afterward, Manalisay volunteered for the submarine force, beginning a military career that would span three years of service aboard three submarines.

The first submarine Manalisay served on was the USS Narwhal (SS-167) which, with Manalisay aboard, was in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, when Japanese planes attacked, bringing the U.S. into World War II. The Narwhal gunned down two planes, and the crew survived.

Soon after, Manalisay was transferred to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where he trained with the crew of the USS Finback (SS-230). The Finback sailed to the Pacific in 1942 and participated in the Battle of Midway, which was the turning point of the Pacific Theater. The Finback also conducted reconnaissance operations around Tanaga, an island in the Aleutian Islands, and Kiska, an island in Alaska invaded by Japan. In one group photograph of the crew, taken in Dutch Harbor, Alaska, the person most likely to be Manalisay is shown not wearing a jacket, braving the Alaskan weather.

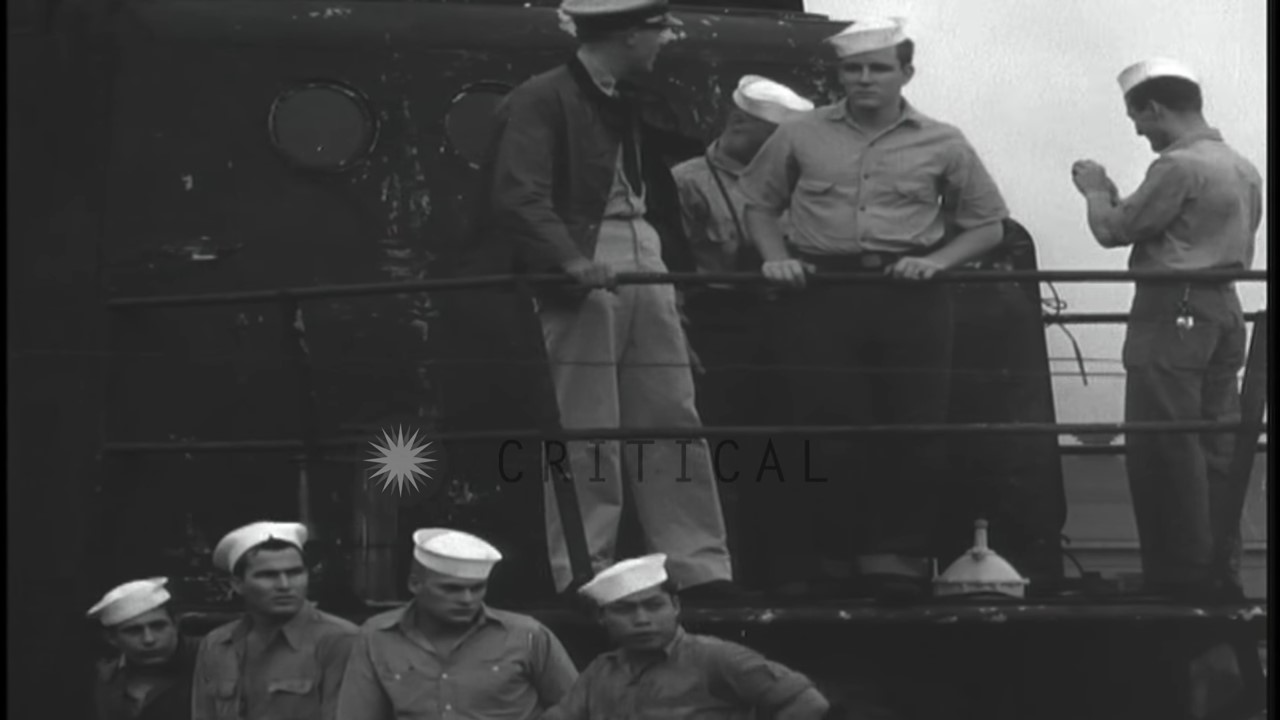

Starting in late 1942, Manalisay served aboard the USS Wahoo (SS-238). The Wahoo, commanded by Dudley “Mush” Morton, was renowned for its aggressive tactics and successes. After its third patrol, the Wahoo sailed into Pearl Harbor with a broom tied to its periscope, indicating a “clean sweep” of ships, a tradition that would be perpetuated by the submarine service. Aboard the Wahoo, Manalisay received his final promotion to the rank of Steward Third Class. During this time, the Wahoo would go on patrol in the waters of New Guinea, Korea, the Kuril Islands, Hokkaido, and ultimately, western Japan.

During the Wahoo’s sixth patrol, it was assigned to the Sea of Japan. Despite sighting many targets, its torpedoes failed to sink the enemy ships due to errors in design.

The Wahoo’s seventh patrol, however, would go down in history. Its mission was, once again, to infiltrate the Sea of Japan, a body of water between Japan, Korea, and Russia, to sink enemy ships. It executed this mission with flying colors, sinking 13,000 tons of cargo on four ships. News of the Wahoo’s success spread via Japanese radio broadcasts. As the Wahoo began its return home in 1943, it had to pass through the Soya/La Perouse Strait, a narrow passageway between the islands of Hokkaido and Sakhalin. After resurfacing, the Wahoo was spotted by Japanese aircraft and sunk by a combination of depth charges and aerial bombs. Unfortunately, all 80 sailors perished, including Manalisay.

Serving on a submarine was one of the most dangerous jobs in the Navy. President Theodore Roosevelt once took a ride in a submarine, and afterward demanded that submariners receive something extra for their treacherous line of work. The work itself was purely voluntary, and as per President Roosevelt’s request, they were given among the best meals aboard any Navy vessel.

It was even more dangerous to be a steward or mess attendant on a submarine. Throughout the Navy, the Steward branch was a racially segregated branch, comprised of African-Americans, Filipinos, and CHamorus.

Submarines played a key role in the downfall of the Japanese Empire. Due to its mountainous geography and lack of arable land, Japan had to look outwards for resources. This included food, oil, and metal—all resources necessary for the modernizing lifestyle of their cities and people. Submarines sank many cargo ships, crippling Japan’s flow of resources and severely weakening their industrial strength.

Manalisay was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart for his heroism and courage and is memorialized in the Courts of the Missing at Pu’owaina, otherwise known as the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, or Punchbowl. Although his body remains underwater, along with the other sailors of the Wahoo, he is considered to be “on eternal patrol.”

Eulogy

The average temperature of the island of Guam is almost always over 80 degrees Fahrenheit. Coupled with the humidity, this provides the native inhabitants of the island, the CHamoru people, with a pleasant tropical climate for living. In fact, because it’s so hot and tropical, people from Guam tend to have a hard time adapting to colder temperatures. In many places off-island, it can feel really cold. Yet, in a group photo of the submarine USS Finback, taken in the freezing cold weather of Alaska, one young CHamoru soldier, despite almost everyone around him wearing a jacket, stood there, braving the cold, without one. This man was most likely Steward Third Class Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay.

Even though Manalisay was limited in his ability to help in the war due to the color of his skin, he still patriotically fought and died not only for the United States but for the hope that the U.S. would eventually liberate his home and his family back on Guam from the horrors of enemy rule. Although Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay didn’t get to live to see the liberation of his island, his efforts contributed to the bigger picture of the war.

Manalisay’s service in the U.S. Navy is a testament to his courage and epitomizes the fact that you don’t have to be well known to be a war hero—most soldiers led silent lives, and made sacrifices and endured hardships that went largely unknown, yet their stories are still profound and heroic in their own ways.

As CHamoru soldiers left Guam, some would sing this song to their mothers and wives, comforting them to wipe their tears because they will be together again.

Basta nana di tumanges

(Mom, stop crying,)

Saosao todu i lago-mu

(Wipe your tears,)

Sa ti o apmam na tiempo

(Because it’s not time yet,)

Siempre i fatto i lahi-mu

(Your son will surely be back.)

Pues adios adios kirida,

(So goodbye, goodbye, darling,)

Pues adios adios adios

(So goodbye, goodbye, goodbye,)

Esta ki matto yu ginen lagu,

(Until I come back from the north,)

Ya ta asagua na dos.

(And the two of us will be together again.)

Jesus, Si Yu’us Ma’ase para i sinetbi-mu.

(Jesus, thank you for your service.)

Na måhgong ni’ taihinekkok na minahgong-ña Asaina.

(Eternal rest grant onto him O Lord,)

Ya ti mamatai na mina’lak u inina.

(And let Perpetual Light shine upon him.)

Ya u såga gi minahgong. Taiguennao mohon.

(May he rest in peace. Amen.)

Reflection

The Sacrifice for Freedom®: World War II in the Pacific program marked one of the most magnificent chapters of my life, and an adventure I will never forget. From the first modules about Commodore Perry’s landing in 1853, and how it eventually led up to the Pacific Theater, to battles during the war such as Singapore, Midway, and the Firebombing of Tokyo, Sacrifice for Freedom has taught me fascinating history over the past year, and it has been such an honor to participate in such an extraordinary program!

Researching our Silent Heroes was a transformative journey and truly made the program special. In learning history, you usually learn about major historical figures—world leaders, generals, and trailblazing pioneers. But researching ordinary people from the past reminds you that World War II, and other periods of history, weren’t just chapters in a book, but people’s lives. Though the research process was challenging, it was totally worth the effort. SFF has shown me the more human aspect of World War II, and I am extremely thankful for that. After all the research, I feel like I could consider my silent hero a friend. Steward Third Class Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay’s story has changed my life and the way I see history.

The program was one of the highlights of my life. As an avid history nerd, learning about World War II history is fascinating, but being in the actual spot where it all began hits differently. It’s a difficult feeling to describe, but it’s one of solemn understanding and moving remembrance. History, being decades in the past, can often seem distant; but not at the Bishop Museum, where Hawaiian history is memorialized for future generations. And not at Pearl Harbor and Punchbowl, where you can listen to the stories of the valiant soldiers who fought and died for our nation during World War II.

For the rest of my life, I will always reflect back on the wondrous days of Sacrifice for Freedom. All the eye-opening experiences, mesmerizing history, joyous memories, and some of the best friends I have ever made—are things that I will forever cherish and hold close to my heart. I have the deepest gratitude for all the organizers and facilitators who made this incredible program possible, and everyone else who was a part of my journey! Aloha and A hui hou!

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Crew of the Finback (SS-230) posing for a shot on 13 August 1942 in Dutch Harbor. Photograph. August 13, 1942. National Archives and Records Administration (80-G-215170). http://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08230.htm.

Guam. Merizo. 1940 U.S. Federal Census. Digital images. http://ancestry.com.

Guam. Merizo. 1930 U.S. Federal Census. Digital images. http://ancestry.com.

Guam Invasion, 1944. Photograph. July 1944. Naval History and Heritage Command (26-G-2684). https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/26-G-02000/26-G-2684.html.

Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay. Defense POW/MA Account Agency, Unaccounted-for Remains, Group B (Unrecoverable), 1941-1975. https://ancestry.com.

Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay. World War II Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Casualties, 1941-1945. Digital Images. https://ancestry.com.

Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay. World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949. Digital Images. https://ancestry.com.

Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay. Wahoo (SS-238), 5/31/42-11/1/43. Muster Rolls of U.S. Navy Ships, Station, and Other Naval Activities, 1/1/1939-1/1/1949. Record Group 24. National Archives and Records Administration (NAID 192700412). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/192700412.

Malesso’ street in a photo taken before World War II. Photograph. Photograph. 1930’s. Guampedia. https://www.guampedia.com/merizo-malesso/#gallery[photonic-flickr-set-1]/3971052616/.

Merizo men paddling to U.S. Navy ships after escaping from Japanese soldiers. Photograph. July 1944. Micronesian Area Research Center. https://www.guampedia.com/war-atrocities-tinta-and-faha-massacres/#gallery[photonic-flickr-set-1]/3985411619/.

Pearl Harbor Attack. Photograph. December 7, 1941. Naval History and Heritage Command (80-G-32704). https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/wars-and-events/world-war-ii/pearl-harbor-raid/attacks-in-the-navy-yard-area/general-views/80-G-32704.html.

“Sailors and officers aboard USS Wahoo which is approaching the submarine base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, February 7, 1943.” Video file, 2:04. YouTube. Posted by CriticalPast. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B3I0Y5NZkZg.

“Sailors cheering aboard USS Wahoo at the submarine base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, February 7, 1943.” Video file, 0:55. YouTube. Posted by CriticalPast. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_npteXhiwXo.

St3c Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay. Photograph. July 15, 1943. On Eternal Patrol. https://www.oneternalpatrol.com/manalisay-j-c.htm.

Thompson, Laura. Beyond the Dream: A Search for Meaning. Guam: Micronesia Area Research Center, 1991.

Thompson, Laura. Guam And Its People. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1947.

USS Narwhal, Report of Pearl Harbor Attack. December 12, 1941. Naval History and Heritage Command. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/archives/digital-exhibits-highlights/action-reports/wwii-pearl-harbor-attack/ships-m-r/uss-narwhal-ss-167-action-report.html.

USS Wahoo (SS-238). Photograph. July 14, 1943. Naval History and Heritage Command (19-N-48940). https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nara-series/19-n/19-N-40000/19-N-48940.html.

Secondary Sources

Babauta, Leo. “War Atrocities: Tinta and Faha Massacres, Malesso.” Guampedia. Updated May 24, 2022. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.guampedia.com/war-atrocities-tinta-and-faha-massacres/.

Borja, Paul J. “War in the Pacific NHP: Liberation — Guam Remembers. Men escape nightmare in Merizo.” National Park Service. Accessed June 10, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/npswapa/extcontent/lib/liberation14.htm.

Broderick, Justin T. “U.S. Navy World War II Enlisted Rates: Messman/Steward Branch.” Updated 2013. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.uniform-reference.net/insignia/usn/usn_ww2_enl_steward.html.

Cressman, Robert J. “Finback I (SS-230).” Naval History and Heritage Command. Updated April 14, 2020. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/f/finback.html.

Guam Historic Preservation Office. “The Massacre at Faha.” National Park Service. Accessed April 16, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/npswapa/Guam/Cave%20massacres/Faha.htm.

Havern, Sr., Christopher B., and Robert J. Cressman. “Chaumont (AP-5).” Naval History and Heritage Command. Updated May 31, 2018. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/c/chaumont.html

Hinman, Charles R. and Paul W. Wittmer. “On Eternal Patrol – The Loss of USS Wahoo (SS-238).” On Eternal Patrol. Accessed June 1, 2022. http://www.oneternalpatrol.com/uss-wahoo-238-loss.htm.

Hinman, Charles R. and Paul W. Wittmer. “On Eternal Patrol – Lost Submariners of World War II. Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay.” On Eternal Patrol. Accessed June 1, 2022. http://www.oneternalpatrol.com/manalisay-j-c.htm.

Howe, Therese Padua. Napu Blas and Mr. Lazaro Quinata holding Manalisay’s memorial on the Courts of the Missing at Pu’owaina, HI. Photograph. July 30, 2022. Pacific Daily News. https://www.guampdn.com/lifestyle/on-eternal-patrol-chamoru-wwii-submariner-jesus-chargualaf-manalisay/article_86f26c8c-0fa8-11ed-a1a1-ff7ccf70bf76.html.

“Jesus C. Manalisay.” American Battle Monuments Commission. Accessed August 18, 2022. https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/manalisay%3Djesus.

Plate, Douglas. “Malesso’ (Merizo).” Guampedia. Updated May 18, 2022. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.guampedia.com/merizo-malesso/.

Rogers, Robert F. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam, Revised Edition. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2011.

Sentimental Journey 4 – Guam Songs Remembered. KUAM News. July 30, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YjS31e7-bzo&t=922s.

“ST3 Jesus Chargualaf Manalisay.” Find a Grave. Updated January 7, 2007. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/17340851/jesus-chargualaf-manalisay.

“Wahoo (SS-238).” Naval History and Heritage Command. January 31, 2017. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/u/united-states-submarine-losses/wahoo-ss-238.html.