Private Melina Olive Shaw

- Unit: Signal Corps

- Date of Birth: June 27, 1890

- Date of Death: July 10, 1980

- Hometown: Adams, Massachusetts

- Award(s): World War I Victory Medal

- Cemetery: Section 1, Grave 1. Massachusetts National Cemetery, Buzzard's Bay, Massachusetts

Hingham High School

2017–2018

Before the War

Born in Adams, a small town in the Berkshires region of western Massachusetts, Melina Olive Girard, known as Olive, was the youngest of four children born to Dr. George and Mrs. Adele Girard. Her father was born in Quebec, Canada and her mother was from Champlain, New York, a town just south of the Canadian border. Likely, they spoke French, and though they died young — her father of “heart trouble and paralysis” just before Olive turned two, and her mother of tuberculosis just after Olive turned twelve _ Olive grew up with these roots.

She learned conversational French from one of her father’s medical assistants. In 1909, at age 19, she married James Blaine Shaw of Dexter, Maine. They lived with Olive’s sister Georgine and her husband, Warner Douglass, a photographer and booking agent for Moving Picture Company, which later became Loews Theatres. James and Olive quickly divorced.

A 1979 newspaper article noted that Olive studied at the Sorbonne in Paris before the war. Archives at the New England Conservatory note that she studied piano and French for four terms between 1912 and 1914. Olive wrote that she was a student at the New England Conservatory in 1917 when she heard about the need for French-speaking women to serve overseas with the American Expeditionary Force as telephone operators. Olive became one of them.

Military Experience

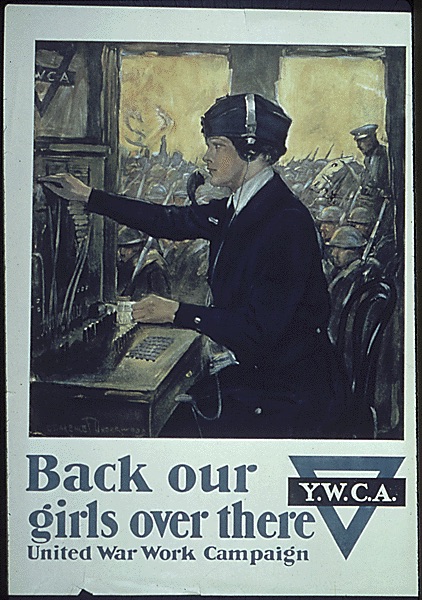

Women have always contributed to American war efforts. Prior to World War I, however, the United States military did not employ women in any capacity other than nursing. With the introduction of telephone communication in World War I, this policy changed.

Demand for Telephone Operators

At first Americans relied upon French women working as telephone operators to help them communicate at the front. According to historian Jill Frahm, because of “the operators’ limited command of English…and the differences in the pace and efficiency of work characteristic of the two cultures,” the U.S. Army turned to its own ranks, filling telephone operator positions with enlisted men. This did not improve the situation. The men were neither bilingual nor trained on the technology.

To address its shortage of telephone operators overseas, the U.S. Army Signal Corps recruited women who could also speak French. Captain E.J. Wesson, who recruited the women to serve as operators noted, “They are going to astound the people over there by the efficiency of their work. In Paris it takes from forty to sixty seconds to complete one call. The girls are equipped to handle 300 calls an hour.”

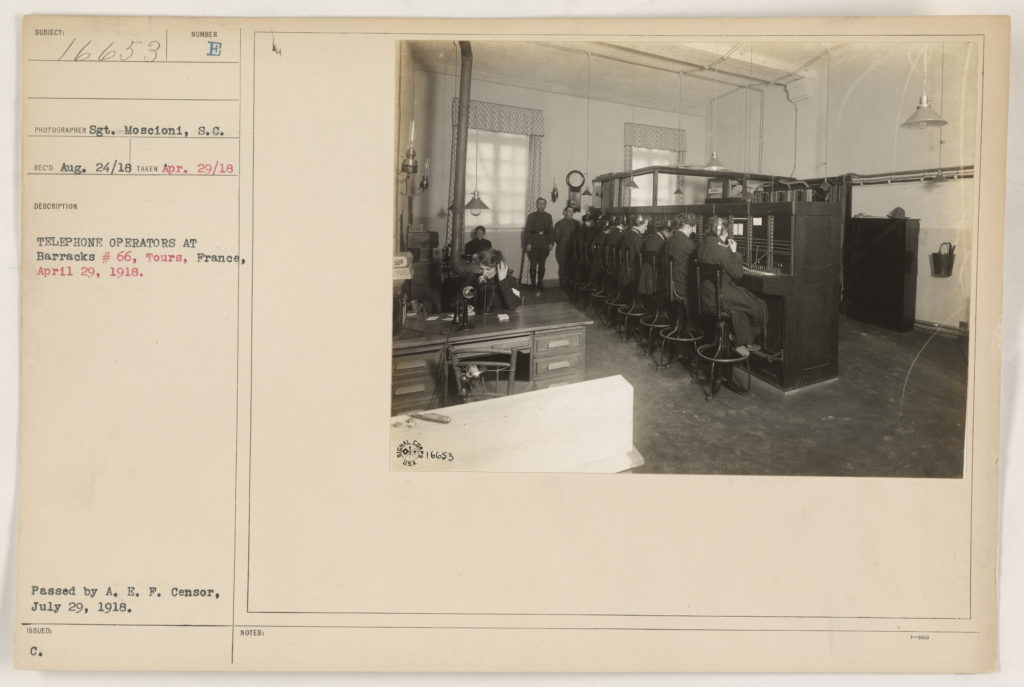

All over France, telephone lines kept front line soldiers in touch with commanders and supply depots. The process was cumbersome, the communications were coded, and the volume of calls was tremendous.

The War Department resisted recruiting American women and faced significant pressure from individuals and groups who believed that women would have negative, even dangerous, effects on male American soldiers. Historian Elizabeth Cobbs quoted correspondence from an Illinois Christian group to the War Department:

“‘We…respectfully petition you to help keep our boys clean; not only from the ravages of the liquor traffic, but the scarlot [sic] woman as well. We have sincerely given you our best and we sincerely trust you will not only use them, but protect them from these forces that are more deadly that the armies of Europe, inasmuch as they destroy both body and soul.’ ”

General John J. Pershing personally requested the assistance. He claimed that “the women who go into the service will do as much to help win the war as the men in khaki.” As a result, 233 Signal Corps operators, known as Hello Girls, served in the American Expeditionary Force during World War I.

Shaw applied to the United States military to serve in the Signal Corps in January 1918. Applicants needed to speak French and pass exams to prove their fluency. Successful candidates received telephone training before they traveled to France.

Shaw was accepted and sworn into service with the military oath, and trained in Lowell, Massachusetts, at the New England Telephone Company. Shaw transferred to AT&T headquarters in New York City, was sworn in again, and quartered in Hoboken, New Jersey, to wait for orders to cross the Atlantic.

In New York, Shaw was fitted for her uniform. Strictly regulated, these uniforms included a blue Norfolk jacket, long skirt, Army boots, hat, overcoat, wool undergarments, and bloomers. In a 1977 affidavit, Shaw described, “We wore regulation Army Signal Corps bronze devices on our collars and overseas caps, as well as the regulation ‘U.S.’ on our collars. These were the same as were worn by male Army Signal Corps officers.” Shaw was incredibly proud of her uniform.

Shaw sailed to France in the second group of operators, under the command of Chief Operator Inez Crittenden. They sailed on the HMS Aquitania and arrived in April. Shaw and her fellow operators traveled to St. Nazaire and then transferred to Brest, where Shaw worked for over four months before she was hospitalized in Tours.

After her release she worked in Tours as an operator and translator. She fell ill again with a terrible cold contracted around the time she spent two hours standing in cold rain in formation for inspection by General Pershing. She was discharged on May 5, 1919, and returned home. Her Chief Operator, Inez Crittenden, was not as lucky. She died in Paris on the day of the armistice, likely from influenza-related complications.

The U.S. War Department considered the women serving in the Signal Corps to be civilian employees, but they were never told this. Military publications referred to them as servicemembers. A March 29, 1918 article in Stars and Stripes discussed the first group of Hello Girls who arrived in France: “They arrived just the other day and like everything else that’s new and interesting about the Army — yes, they’re in it too — they were lined up before a Signal Corps camera and shot.”

The Hello Girls were subject to military discipline, had to be approved for leave and wear their uniforms on leave. They earned less than civilian employees and could not resign. As Shaw recalled in a 1950 memo she prepared for the Armed Services Committee, “We ate army food, slept in army barracks and worked seven days a week. Lights went out at nine and we all had to be up at seven to eat with the army personnel. Could not leave camp without a permit, and then only on rare occasions.”

Some Hello Girls served near the front lines in hazardous conditions. Captain Wesson explained in a newspaper interview, “As they assist in the giving of commands concerning artillery direction and calling up of reserves, they have a tremendously responsible position. The morale of the unit is of the finest, and they did not come into it without facing the possibility of danger.” During the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the building where the operators worked caught fire. The women refused to leave their switchboards at first, and returned to work once the fire was extinguished.

Veteran Experience

Back in the United States, Shaw was diagnosed with tuberculosis and pernicious anemia. She was hospitalized for two years, part of that time at Parker Hill Hospital, run by the War Department. A passenger list from the SS Statendam noted her travel from Boulogne-sur-Mer to New York City in October 1930. Eventually, Shaw served in Washington, D.C. as the personal secretary to Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers of Lowell, Massachusetts. Shaw’s World War I experience surely influenced Congresswoman Rogers’s introduction of legislation to create the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in 1941.

For their service in dangerous wartime conditions, the Hello Girls received praise from Colonel Parker Hitt, Brigadier General Edgar Russel, and General John Pershing. In General Orders No. 73 from April 30, 1919, Pershing wrote, “The part played by women in winning the war has been an important one…Whether ministering to the sick or wounded, or engaged in the innumerable activities requiring your aid, the cheerfulness, loyalty and efficiency which have characterized your efforts deserve the highest praise.” Seven women received Distinguished Service Medals for their work. When they returned home, however, did not receive Victory Medals or discharge papers. Their military rescinded their war risk insurance policies. They would not be considered veterans.

When hospitalized at a military hospital after returning to the U.S., Shaw was treated as a “public health patient,” and incurred personal costs for her medical treatment. In a 1921 letter on Shaw’s behalf to the American Legion National Legislative Committee in Washington, D.C., a local American Legion official noted, “Also, she has paid out money to civilian doctors, and should be reimbursed for that. There are 150 other ladies in the same plight, Miss Shaw having knowledge of some of the cases. If the regulations now existing afford no relief, there should be provisions made for the recognition and compensation of those who gave their effective service, thereby releasing for other duty, men who could be better used elsewhere.”

Led by Merle Egan Anderson, the women began the fight for recognition as veterans. After 60 years, the government issued the women honorable discharges. In that time, more than 50 bills were filed in Congress to grant the Hello Girls veteran status, but none succeeded.

In 1975 Attorney Mark Hough learned of their battle after reading an article about Merle Anderson in the Seattle Times. He contacted her and offered to serve as their pro bono counsel. Building a case that included statements from several of the surviving Hello Girls, Hough pressured Congress to take action before he filed the case. Congress scheduled hearings and Mark Hough made a statement to the Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs on May 25, 1977. He noted it was his “belief that a gross injustice has been done to the women of the Signal Corps Telephone Operating Units…there is no question in my mind that the Signal Corps Telephone Operators morally and legally are entitled to official recognition of their military service in the United States Army.”

In November 1977, the GI Improvement Act of 1977, signed by President Jimmy Carter, officially recognized the Hello Girls as veterans. In 1979, the Hello Girls were finally recognized as having been on active duty during World War I.

Olive Shaw, 89 years old, received her honorable discharge and victory medal from Major General Hugh F. T. Hoffman, Jr. on August 23, 1979 at the Littleton House nursing home in Littleton, Massachusetts. “It took a long time,” she remarked. Sadly, she was one of only 18 women still alive to receive this recognition. Reporter Renda Mott of the Worcester Telegram described Shaw’s reaction: “While cameras clicked and the spectators applauded, Miss Shaw could only mumble ‘Great, wonderful’ as a few tears ran down her cheeks. The document will hang in honor over her bed, she said.”

Commemoration

Olive Shaw died less than a year later on July 10, 1980. In October 1980 the new Massachusetts National Cemetery opened in Bourne, Massachusetts, at Otis Air Force Base. Melina Olive Shaw was the first veteran to be buried there in Section 1, Plot 1.

According to historian Elizabeth Cobbs, “Olive Shaw’s uniform was the crowning evidence” that gave the Hello Girls their rightful status as veterans of World War I in 1979. Today, it is on display in the National World War I Museum & Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri.

In June 2018, Senator Dean Heller of Nevada and Senator Jon Tester of Montana introduced legislation to award the Congressional Gold Medal to the Hello Girls of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Senator Tester stated, “They blazed a new path for women on the front lines in France, and the Congressional Gold Medal will honor their service as well as their fight for recognition.” This award is the highest honor Congress can bestow upon civilians.

Bibliography

“Awards, Honors, & Medals.” United States Senate. Accessed August 16, 2018. www.senate.gov/reference/Index/Awards_Honors_Medals.htm.

Back our girls over there. Y.W.C.A. United War Work Campaign. Poster. c.1917–1919. National Archives and Records Administration (512611). Image.

Birse, Ken. Telephone interview with author. August 23, 2018.

Cobbs, Elizabeth. The Hello Girls: America’s First Women Soldiers. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017.

Collins, Elizabeth. “World War I’s Hello Girls: Paving the Way for Women in the U.S. Army.” Soldiers Magazine, March 2014. soldiers.dodlive.mil/2014/03/world-war-is-hello-girls-paving-the-way-for-women-in-the-u-s-army/.

Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, May 1918. Fold3.com. Digital Images. fold3.com.

Frahm, Jill. “The Hello Girls: Women Telephone Operators with the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I.” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Vol. 3, No. 3 (July 2004): 271–293.

Gavin, Lettie. American Women in World War I: They Also Served. Niwot: University Press of Colorado, 1997.

George Girard. Massachusetts, Death Records, 1841–1915. New England Historic Genealogical Society; Boston, Massachusetts; Massachusetts Vital Records, 1840–1911. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

“Gets Honorable Discharge.” Lowell Sun, August 24, 1979.

“Hello Girls Here in Real Army Duds.” The Stars and Stripes (Paris, France), March 29, 1918.

Jensen, Kimberly. Mobilizing Minerva: American Women in the First World War. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Journal of the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Boston: Wright & Potter, 1919. https://books.google.com/books?id= CdAAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

“Littleton Woman Discharged 61 Years Later.” Times Free Press (East Pepperell, MA), August 29, 1979. Women In Military Service For America Memorial Foundation Historical Files.

Massachusetts. Middlesex County. 1910 U.S. Census. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

Massachusetts. Suffolk County. 1940 U.S. Census. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

Moscone, Sergeant. Telephone operators at Barracks #66, Tours, France. Photograph. August 24, 1918. National Archives and Records Administration (111-SC-16653-ac). Image.

Olive Shaw, World War I Master Index Card, DD214, Official Military Personnel File, Record Group 92; National Archives and Records Administration — St. Louis.

M. Olive Shaw in uniform. Photograph. c. 1918–1919. M. Olive Shaw Collection, Gift of Elsie Daly, Women In Military Service For America Memorial Foundation. Image.

Moody’s Manual of Railroads and Corporation Securities, Vol. 3, 19th Annual Number, Industrial Section. New York: Moody Manual Company, 1918. https://books.google.com/books?id=3_NEAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Mott, Renda A. “The Army Finally Says ‘Well Done.'” Worcester Telegram, August 24, 1979. Women’s Memorial Foundation Historical Files.

New York, Passenger Lists, 1820–1957. Ancestry.com. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Perrin-Mohr, Maryalice. New England Conservatory Archivist. Email message to author. August 20, 2018.

Roberts, W. M. W. M. Roberts to D. A. Little, Phoenix, AZ, January 17, 1921. National WWI Museum & Memorial.

Schneider, Dorothy and Carl J. Into the Breach: American Women Overseas in World War I. New York: Viking, 1991.

Schoettler, Ellouise. Playwright. Email message to author. April 25, 2018.

Shane III, Leo. “Ignored for decades, WWI heroines could be recognized with Congressional Gold Medal.” Military Times, July 5, 2018. www.militarytimes.com/veterans/2018/07/05/ignored-for-decades-wwi-heroines-could-be-recognized-with-congressional-gold-medal/.

Shaw, Olive. “Arguments by Olive Shaw Who Worked for Edith Nourse Rogers to Be Presented to Armed Services Comm., 1950.” National WWI Museum & Memorial, Accession 2015.121 (Papers of Mark Hough), Kansas City, Missouri.

Spruyt, John. National Cemetery Administration. Email message to author. March 9, 2018.

“Statement of Mark M. Hough in Support of Enactment of S. 1414, before the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, United States Senate.” May 25, 1977. Women’s Memorial Foundation Historical Files.

Tel. Operator Files; Office of the Chief Signal Officer Correspondence, 1917–1940, Record Group 111 (Boxes 396–401); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

U.S. Army WWI Transport Service Passenger Lists. Ancestry.com. Digital Images. http://ancestry.com.

U.S. Congress. Senate. Hello Girls’ Congressional Gold Medal Act of 2018. S 3136. 115th Cong., 2nd sess. Introduced in Senate June 26, 2018. https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/s3136/BILLS-115s3136is.pdf.