Sherwin J. Ball

- Date of Birth: March 22, 1920

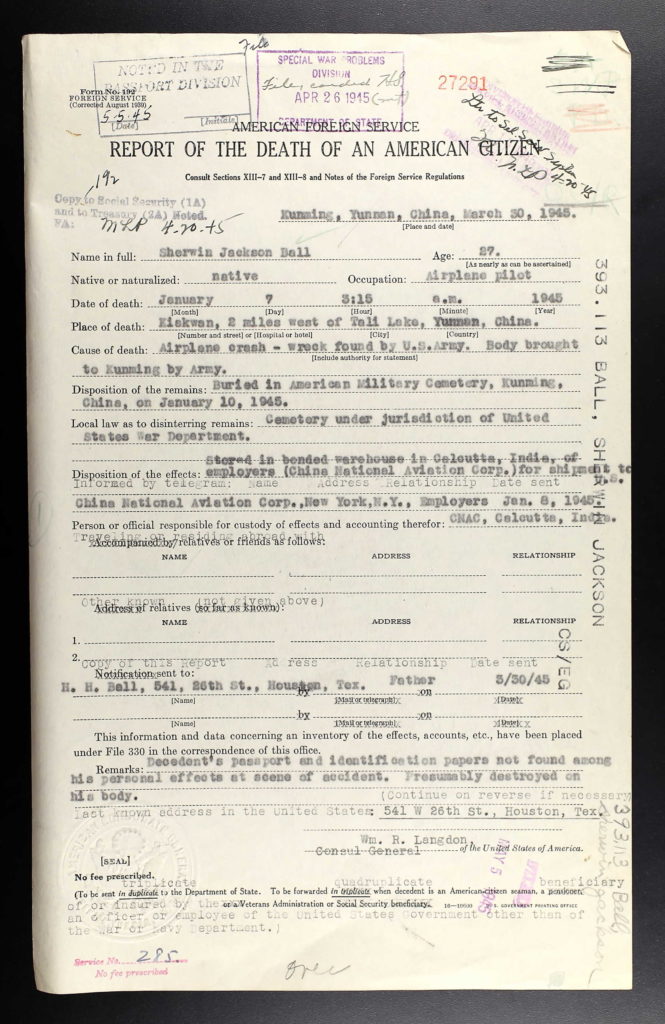

- Date of Death: January 7, 1945

- Hometown: Houston, Texas

- Place of Death: Yunnan Province, China

- Cemetery: Section Q, Grave 357. National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, Honolulu, Hawai'i

Mentored by Ms. Megan Souchek

New Caney High School

2021–2022

Early Life

Sherwin J. Ball was born on March 22, 1920, in Houston, Texas. He lived with his parents, Henry and Daisy Ball, and his brothers Leo and Ray. He attended the University of Houston and later took a job at Hughes Tool Company, a drill-bit manufacturing company headed by the famous aviation innovator Howard Hughes, in his hometown.

Homefront

Ball’s hometown was Houston, Texas. Houston was a developing blue-collar town that became highly industrialized during World War II. The community was involved in several forms of wartime manufacturing, including shipbuilding and the production of uniforms, soap, and water canisters for the U.S. military.

Even as Texas was becoming increasingly industrialized, agricultural production also increased as a result of the war. Home canning was the main form of food production. Since many families already lived on farms, many simply packaged up all kinds of food from their own gardens. In addition, Houston’s growth led to the establishment of the Texas A&M College System, which further advanced the region’s agricultural production by discovering more efficient farming methods and more resilient crops.

The community dramatically changed socially and economically as a result of the war. Wartime production not only helped Houston’s economy recover from the Depression, but it also transformed it into a manufacturing hub for the south that still endures today. This industrialization also incorporated more women into the workforce, advancing the city’s social structure. As more women began to hold jobs historically held by men, they began to demand equal treatment and civil liberties. While it would still be years before social conditions for women truly improved, these events empowered women and set in motion future calls for equal rights in Houston.

industrial hotspot during the war, 1930.

Military Experience

While many of our nation’s heroes either signed up to fight or were drafted, Ball’s experience was unique in that he never officially joined the military, but instead joined the fight as a civilian pilot flying supply missions.

By the time Ball joined the military, several volunteer flight programs had been established. Pilots were direly needed in all theatres of the war, and recruiting civilians to fly helped reduce the strain on the military’s supply of pilots.

Background

In the Asian Theatre, Japanese forces cut off all land routes to China in preparation for an invasion. Japan’s strategy was to weaken China by interrupting the supply of ammunition flowing into the country from the Allied powers. The only way to get supplies in was by flying an extremely dangerous path through the Himalayan mountains, a route nicknamed “The Hump.” In a collaboration between Pan-Am and the China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC), a civilian training program called the First American Volunteer Group was established to recruit pilots to fly this route.

Service

Records suggest that Ball joined this program in the early 1940s. Ball spent the entirety of his service with a subgroup called The China Air Task Force nicknamed the Flying Tigers. In 1944, Ball was promoted to CNAC Captain, and from then on he piloted his own missions across The Hump. Unfortunately, there are few records of Ball’s missions, mainly because of the relatively small size of the program.

Eulogy

During a routine flight on January 7, 1945, Ball’s C-47 Skytrain lost radio contact at 3:15 a.m. It was later discovered that the plane went down in Yunnan Province, China, though the causes of the crash are unknown to this day. The wreckage was found a day later by a fellow CNAC pilot who reported that Ball and his two flight assistants had been killed. Ball was initially buried at an American cemetery in Yunnan Province, China, but Ball’s family later had him formally laid to rest at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific.

Sherwin J. Ball gave his life in one of the most perilous operations of the Pacific Theatre. In all, he piloted 30 round-trips across the Himalayas, and his sacrifice, along with the sacrifices of his fellow CNAC airmen, helped fend off an impending Japanese invasion of one of the last allied powers in the Pacific, an event which would have fundamentally changed the outcome of the war. Ball’s acts of service exceeded what is expected from a civilian. His selfless actions helped change the course of the war not only for his country but for the entire world.

Reflection

It was very difficult for me to summarize my experiences with Sacrifice for Freedom®: World War II in the Pacific program over the past year. Throughout the year and especially on the trip, we acquired so much knowledge from so many different areas of Pacific history that I’m just now beginning to digest it all! However, if I had to name two of the most important takeaways for me from this program, it would be: 1) Heroes aren’t born heroes, and 2) wars are fought mostly because of loyalty and trust in one’s country, not because the other side is inherently bad/good.

Heroes aren’t born heroes. What this means is no matter how intelligent or incredibly brave a soldier seems to be, it is important to realize that they started off as normal citizens. I learned this from researching my silent hero Sherwin J. Ball. It’s hard to believe that even though he valiantly flew supply missions over the Himalayas dozens of times, he started off as a kid in Houston, Texas, just like me. Ball wasn’t born a hero, but he certainly became one. Ball’s journey has reminded me that I don’t have to be afraid to fight for my country should I be called to do so, because I’ve learned that even regular citizens go on to make big differences in wars. Researching my silent hero, as well as studying several books and visiting memorial sites, has further increased my respect for veterans and active military personnel, and I hope to advocate for their remembrance in the future.

Another important thing I learned from this program is that there is rarely and “good” side and a “bad” side in a war. Instead, war is a matter of protecting one’s culture and way of life. I learned that Japan was mainly aggressive towards other countries out of necessity, due to dwindling resources on the island. While this is no excuse for events such as Pearl Harbor, it shows that the general Japanese public simply wanted to live in peace but was acting under the orders of a general who sought to expand the empire at all costs. Again, while this is no justification for violence, it shows that there were good people on both sides of the war. Before this program, I had not been exposed to this idea. This concept has had applications for me far beyond the scope of war. For example, it has shifted my views on the purpose of political parties. Instead of seeing groups of political polar opposites constantly bickering over issues, I see groups with different viewpoints with people on both sides of the aisle that care about the future of the country.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Sherwin Ball. 1936 John H. Regan High School Yearbook. Digital Images. https://ancestry.com.

Sherwin J. Ball. U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Sherwin J. Ball. U.S. Reports of Deaths of American Citizens Abroad, 1835-1974. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Sherwin J. Ball. World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947. Digital Images. https://ancestry.com.

Texas. Houston. 1930 U.S. Federal Census. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Texas. Houston. 1940 U.S. Federal Census. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

USS Houston (CA-30) in Houston Ship Channel. Photograph. 1930. Cruiser Houston Collection, University of Houston Libraries Special Collections. https://digitalcollections.lib.uh.edu/concern/images/dz010q633?locale=en#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&xywh=-348%2C-460%2C6956%2C5992.

Secondary Sources

“1936–1945 – Texas Farmers Fight: Depression and War.” Texas A&M Agrilife. Accessed April 18, 2022. https://agrilife.org/wp-content/uploads/1936-1945.pdf.

Boston, Michael R. Labor, Civil Rights, and the Hughes Tool Company. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2005. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Labor_Civil_Rights_and_the_Hughes_Tool_C/pHJ2ZGH95I4C?hl=en&gbpv=0.

Chapman, Betty T. “Early Houston manufacturers met need for wartime necessities.” Houston Business Journal, February 18, 2011. https://www.bizjournals.com/houston/print-edition/2011/02/18/early-houston-manufacturers-met-need.html.

Draut, Joel. “A Glimpse of Houston during World War II.” The Houston Review, 2012. https://houstonhistorymagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/a-glimpse-of-houston.pdf.

Moore, Tom. “Sherwin J. Ball.” China National Aviation Corporation. Accessed April 18, 2022. http://www.cnac.org/ball01.htm.

“Sherwin J Ball.” National Cemetery Administration. Accessed March 3, 2022. https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/.

“Texas in World War II.” Texas Historical Commission.” Texas Historical Commission. Updated March 12, 2021. Accessed April 18, 2022. www.thc.texas.gov/preserve/projects-and-programs/military-sites/texas-world-war-ii.

Wiggins, Melanie. Torpedoes in the Gulf: Galveston and the U-boats, 1942-1943. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1995.