Technician Fourth Grade Wilfred Masao Motokane

- Unit: Allied Translator Interpreter Section, 306th Counter Intelligence Corps Detachment

- Service Number: 30107747

- Date of Birth: July 12, 1915

- Entered the Military: January 3, 1944

- Date of Death: August 13, 1945

- Hometown: Honolulu, Hawai'i

- Place of Death: Okinawa, Japan

- Cemetery: Section D, Grave 248. National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, Honolulu, Hawai'i

Mentored by Mr. Jason Duncan

Mililani High School

2021-2022

Early Life

A New Home

On July 12, 1915, Masao Motokane was born in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. The son of first generation immigrants from Japan, Motojiro and Mitsuno Motokane, Masao Motokane had four sisters and one brother. Motojiro, Mitsuno, and their first daughter Yoshiko, were all born in Hiroshima prefecture, Japan.

The Motokanes first lived in Kahuku village on the north side of the island of Oahu, where Motojiro Motokane worked on the plantations as a laborer. Motojiro and Mitsuno Motokane’s daughter Shizuko and first son Sadao were born in Kahuku. They then moved to Honolulu, on the south side of Oahu, sometime after 1913.

In his early years, Masao Motokane attended Kalakaua Intermediate School. He then attended McKinley High School, where he was a member of many clubs and student organizations. Motokane also played baseball in the local Japanese-American baseball leagues. He was a pitcher and earned many trophies. As a member of the graduating class of 1933, Masao Motokane received a certificate of honor.

The Motokane family were Japanese American Buddhists. Motokane’s older brother Sadao attended a high school run by the Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-ha sect of Buddhism, and his sister Yoshiko was married at a temple of the same denomination. Almost 200 Buddhist temples supported the many first (Issei) and second generation (Nisei) Japanese Americans living on the islands. Along with religious services, these temples offered Japanese language classes and other support services for the community.

Motokane then attended Margaret Dietz Commercial School. There, he continued his heavy involvement in student activities. He oversaw the hosting of multiple school dances, held the position of student body first vice president, and won fourth place in a shorthand writing contest.

Starting a Family

On February 16, 1937, Masao Motokane married Shizuye Nakamura from Kaneohe, Hawaiʻi. The family lived in Honolulu and Masao Motokane worked as a substation mail clerk on Merchant and Richards Streets in Honolulu. The couple had a child, Wilfred Masao Motokane, Jr., on September 15, 1937, at St. Francis Hospital. In 1943, Masao and Shizuye Motokane changed their names to Wilfred Masao Motokane and Sheila Shizuye Motokane.

Homefront

Wilfred Motokane’s hometown of Honolulu, Hawaiʻiwas the bustling capital city of the Territory of Hawaiʻi. Locals surfed and flocked to the nearby district of Waikiki. The U.S. Military had a large presence on the island of Oahu.

Japanese Attack Leads to Martial Law

Hawaiʻi and the Japanese American Buddhist community were never the same after December 7, 1941. On this day, the naval base at Pearl Harbor and other military installations in the Hawaiian Islands were attacked by the Japanese military, causing U.S. entry into World War II. That same day, Buddhist temples in Hawai’i had expected to continue making preparations for Bodhi Day or Jodo-e, traditionally celebrated on December 8. Bodhi Day (Jodo-e), was the day Siddhartha Gautama, the founder of Buddhism, became enlightened.

The attack on Pearl Harbor had major implications for Hawaiʻi. Martial law and a military government was established following the attack on Pearl Harbor. People living in the Hawaiian Islands now had a curfew, needed to carry identification, and had their freedoms restricted.

Suppression of Buddhism

Even before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans were deemed threats by the U.S. government. Japan’s increasing power in Asia and Hawaiʻi’s large Japanese-American population prompted concern and suspicion. The attack on Pearl Harbor only exasperated this suspicion.

Japanese American Buddhists, like the Motokane family, were seen as a threat because the Buddhist community was deeply connected to Japanese culture. The community was deemed a threat, and the first person arrested after the attack on Pearl Harbor was a Buddhist priest. Eventually, almost all of the Buddhist clergy was arrested and interned in camps, severely impacting the religious services and support system that the Japanese-American community had relied on for decades. The wives of the Buddhist clergy and Buddhists who weren’t arrested persevered and continued religious services, but martial law and the government did not allow many Japanese Americans, and even fewer Buddhists, to gather, limiting their efforts.

Numerous temples shut their doors, others were taken by the government, and some were subject to vandalism and arson. Japanese Americans arrested by the U.S. government, including Buddhist clergy, were held at internment camps on Sand Island and Hono‘uli‘uli and many were sent to the mainland.

Varsity Victory Volunteers and the 100th Infantry Battalion/ 442nd Regimental Combat Team

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, many local Japanese Americans chose to defend their country. In Hawaiʻi, Japanese American ROTC students defended important facilities as a part of the Hawaiʻi Territorial Guard. In 1942, the Hawaiʻi Territorial Guard disbanded and then re-formed the next day. The only difference was that there were no Japanese Americans.

After a successful petition to the military governor of Hawaiʻi, the Varsity Victory Volunteers (VVV) was formed. This group of over 100 Japanese Americans performed various tasks such as construction for the military. At the same time, the 100th Infantry Battalion, a mostly Japanese American unit from Hawaiʻi, impressed U.S. officials with their performance while training. The contributions of the VVV and the performance of the 100th Battalion convinced U.S. officials to allow more Japanese Americans to join the Armed Forces.

In 1943, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) was created, with the goal of recruiting more than 1,000 soldiers from Hawaiʻi and more from California. 10,000 Japanese-Americans showed up to volunteer just from Hawaiʻi. The soldiers who made up the 100th Battalion and 442nd RCT would become the unit with the most awards, for the amount of time served and how big the unit was, in the entire U.S. Armed Forces.

Military Experience

Military Intelligence Service Language School

After the U.S. entry into the war, postal workers like Motokane were exempt from the draft. But on January 3, 1944, Wilfred Motokane volunteered for the U.S. Army. He and 44 other Japanese Americans working for the local postal service decided to volunteer together. These men set the record for the percentage of a workplace who volunteered for the U.S. Army.

A month later, Wilfred started training at the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) at Camp Savage, Minnesota. This class was the largest ever in the school’s history. The course covered many aspects of the Japanese language including reading, writing, speaking, and translating different styles of Japanese. The duration of the training was also increased from six to nine months with the start of Motokane’s class. After graduating from the MISLS in November 1944, Wilfred completed eight weeks of basic training at Fort McClellan, Alabama.

Deployment to the Philippines

After his training was complete, Wilfred Motokane was assigned to the ATIS (Allied Translator and Interpreter Service), and deployed to the Philippines in early 1945. Motokane was deployed as the U.S. was approaching the Japanese mainland. In mid-1945, the U.S. started to develop a contingency plan, called Operation Blacklist, in case Japan decided to surrender without the need of a full Allied invasion of the Japanese mainland.

Final Stages of the War

On August 6, 1945, after the Japanese government did not agree to Allied demands to surrender, an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, instantly killing around 140,000 people. At least 74,000 more people were killed after a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki on August 9. Thousands were injured, and thousands more died later from radiation poisoning.

Following the two atomic bombings and the declaration of war by the Soviet Union, an Imperial Council was called in Japan. Due to an even split on what Japan should do within the council, Emperor Hirohito broke the tie and voted to surrender on August 10, 1945.

Plane Crash in Okinawa

Motokane was assigned to the 306th Counter Intelligence Corps Detachment (CIC). This unit was attached to the 11th Airborne Division.

On August 12, 1945, Motokane and 29 others were driven to Clark Airfield, located on Luzon, in the Philippines. They then boarded a Curtiss C-46 Commando headed to Okinawa. This was part of a larger effort to fly the 306th CIC Detachment and the 11th Airborne to Okinawa in preparation for a potential Japanese surrender, and thus, the order to carry out Operation Blacklist.

Earlier that day, the airfield where they were supposed to land, outside of Naha, Okinawa, weathered Japanese kamikaze attacks. The airfield was located on cliffs, obscured by smoke from damaged ships, and blacked out due to the earlier kamikaze attacks. The pilot of Motokane’s plane tried to land at the airfield three times. On the third try, the plane crashed into the cliff, killing all 30 people on board.

End of the War

On August 15, 1945, both President Truman and Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender of Japan and Operation Blacklist began. The 11th Airborne Division and its CIC attachment, not including Motokane and the other soldiers lost in the crash, landed at Atsugi airdrome near Tokyo later that August, becoming some of the first American troops in Japan.

Honoring the Fallen

Technician Fourth Grade Motokane was awarded the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal and Ribbon and the World War II Victory Medal and Ribbon. However, because Motokane died in a non-combat incident, he did not receive the Purple Heart. Motokane’s memorial service was held at the Honpa Hongwanji Hawaii Betsuin (one of the main branch temples for the Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-ha sect of Buddhism) on Fort Street, on September 2, 1945. Due to the sacrifices made by so many Japanese American soldiers, the government in Hawaiʻi was pushed to cut back its restrictions on gatherings that had severely affected the Buddhist community.

Technician Fourth Grade Motokane was given both a Homyo (Buddhist Name) and an Ingo (Honorary Posthumous Title). While a Homyo can be given to anyone who is willing to learn from the Buddhist teachings, an Ingo is only given to those who have passed away and who have done something of great importance. It is most likely that Motokane’s Honorary Posthumous Title (Ingo) was personally chosen by the Gomonshu (head religious leader of the Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-ha sect of Buddhism), who resides in Japan. Technician Fourth Grade Motokane’s Ingo (Honorary Posthumous Title) is Gan-Jō-In, which means “One who sincerely lived in the Vow,” and his Homyo (Buddhist Name) is Shaku Yū-Shō, which means “One who is a disciple of Shakyamuni Buddha – Right Courage”. Together they make his full title: Gan-Jō-In Shaku Yū-Shō (願誠院 釋勇昌).

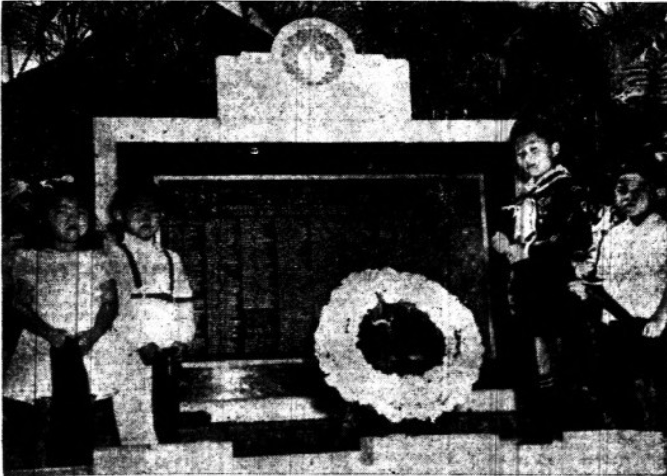

The Jodo Shinshu Buddhist community honored Motokane and the 373 other Buddhist soldiers who lost their lives during the war with a ceremony in 1948. Motokane’s 10-year-old son, Wilfred Motokane, Jr., and three other children were given the opportunity to unveil the plaque memorializing their fallen loved ones on May 30, 1948. The unveiling ceremony was attended by representatives from the Territory of Hawaiʻi, City and County of Honolulu, and various community organizations.

The National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific opened in 1949. Motokane’s remains were moved from Okinawa and reinterred in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific on August 24, 1949. Swimmers from the Japanese national swimming team attended the service officiated by Chaplain Hiro Higuchi.

Today, Technician Fourth Grade Wilfred Masao Motokane’s name sits on a plaque in front of the Honpa Hongwanji Hawaii Betsuin, on Pali Highway. His final resting place in the Punchbowl crater at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific overlooks this plaque, located a couple streets below the crater.

Eulogy

A few days before Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender of Japan, ending World War II, Technician Fourth Grade Wilfred Masao Motokane was killed in a plane crash on Okinawa. Motokane left behind his parents, siblings, wife, and young child to serve and protect this nation in a time of hardship and need.

His sister Violet, remembered how he used to spoil her, and also his kind and loving nature.

He took part in what was known as Operation Blacklist, the American contingency plan in case Japan surrendered. Major General Ishimoto recalled ten names being posted on a bulletin board. These names, including Motokane’s, were to be assigned to the 306th Counter Intelligence Corps Detachment, attached to the 11th Airborne Division. This group of soldiers were set to be some of the first Americans to land in Japan.

The airfield Motokane was set to land at was located on cliffs, obscured by smoke from damaged ships, and blacked out due to the earlier kamikaze attacks. On the third attempt to land the plane, it crashed into cliffs, tragically killing all 30 people on board, including Motokane.

The two gravestones below of Motokane’s gravestone are two soldiers who also lost their lives in that tragic plane crash, Staff Sergeant Joseph Takeo Kuwada and Technician Fourth Grade Masaru Sogi. All three of these soldiers were Japanese American. They chose to serve and die for this country… the very same country that suspected them and their community of disloyalty and espionage. They saw through the prejudice they experienced to the founding principles of this country that needed defending: freedom, liberty, and justice.

Technician Fourth Grade Wilfred Motokane, and many others who made the ultimate sacrifice for the United States of America deserve our utmost gratitude and respect. Thank you, Technician Fourth Grade Motokane.

Reflection

The live program was a very insightful experience for so many reasons. One of those reasons is that I have learned so much about where I live. All the activities and things we did on this trip provided so much information about Hawaiʻi and the people who lived and served here. I’ll make sure to keep the history of these islands in my mind as I spend my time here. No matter where I go, this program has taught me that every place has its own history that can be learned.

I also learned from the readings, activities, research of a Silent Hero, and live program how much the generations before us have done in order for us to live in this country. Visiting the memorials, learning about my Silent Hero and other Silent Heroes, visiting museums, etc has demonstrated how lucky we are to call the United States our home. After these experiences I’ll make sure to apply a sense of gratitude and thankfulness in everything I do moving forward. The program really showed that we can’t take anything for granted, and that the sacrifices so many have made should never be forgotten.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

“100 Per Cent of Post Office Men Here Volunteer.” Hawaii Times [Honolulu, Hawaii], February 2, 1943. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tht19430202-01.1.1&e=——-en-10–1–img——-.

“3,000 Attend Unveiling of Memorial Plaque.” Hawaii Times [Honolulu, Hawaii], May 31, 1948. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tht19480531-01.1.1&e=——-en-10–1–img——-.

“Amateur Ball League Ready For Opening.” Nippu Jiji [Honolulu, HI], January 7, 1938. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tnj19380107-01.1.4&srpos=57&e=——-en-10–51–img-motokane——–.

“The Annual Party Held at Wall Home For Dietz School.” The Honolulu Advertiser [Honolulu, Hawaii], November 18, 1935. Accessed June 1, 2022. www.newspapers.com/image/259069465/?terms=wilfred%20motokane&match=1.

Baba, Daido. Email interview by the author. February 18, 2022.

“Births.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], September 18, 1937. Newspapers.com (275072120).

“Buddhist War Dead Memorial To Be Unveiled.” Hawaii Times [Honolulu, Hawaii], March 5, 1948. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tht19480305-01.1.2&srpos=3&e=——-en-10–1–img-memorial+buddhist+soldiers—-1948–.

CHAP. 339.-An Act To provide a government for the Territory of Hawaii., H.R. Doc. No. 56, 1st Sess. (April 30, 1900). www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/31_stat_141_hawaiian_organic_act_1900.pdf.

“Class Officers Are Chosen At Dietz School.” The Honolulu Advertiser [Honolulu, Hawaii], October 26, 1936. Newspapers.com (259100931).

“Class Plans Reunion.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], April 9, 1931. Newspapers.com (274929676).

“Dietz School to Hold Dance.” The Honolulu Advertiser [Honolulu, Hawaii], June 14, 1937. Newspapers.com (265056952).

“Dietz School Wins Banner in International Contest.” The Honolulu Advertiser [Honolulu, Hawaii], August 26, 1936. Newspapers.com (259217958).

“Dignitaries to Attend Buddhist War Dead Rites.” Hawaii Times [Honolulu, Hawaii], May 29, 1948. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tht19480529-01.1.3&srpos=2&e=——-en-10–1–img-memorial+buddhist+soldiers—-1948–.

Fujimoto, David. Instant messenger interview by the author. September 19, 2022.

Fujio Urata and Yoshiko Motokane. Hawaii, U.S., Marriage Certificates and Indexes, 1841-1944. Digital images. ancestry.com.

“Grace Y. Numazu.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], April 13, 1994. Newspapers.com (273613828).

Hawaii. Honolulu. 1940 United States Federal Census. Digital images. ancestry.com.

Hawaii. Honolulu. 1930 United States Federal Census. Digital images. ancestry.com.

Hawaii Territory. Kahuku. 1910 United States Federal Census. Digital images. ancestry.com.

“Henry Sato Stars As Hinodes Trounce Ramblers By 16 To 15.” Nippu Jiji [Honolulu, HI], May 14, 1935. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tnj19350514-01.1.10&srpos=32&e=——-en-10–31–img-motokane——–.

“Hongwanji Notes Completion of Charnel House.” Nippu Jiji [Honolulu, HI], November 10, 1941. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=A-SH970-004&e=——-en-10–1–img-hongwanji——#.

Ho, Marian. “Valentine Dance At Fuller Hall.” The Honolulu Advertiser [Honolulu, Hawaii], February 17, 1936. Newspapers.com (259071577).

Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii, and Honpa Hongwanji Hawaii Betsuin. Instant messenger interview by David Fujimoto. September 19, 2022.

“HRT Being Sued For Woman’s Death.” Hawaii Times [Honolulu, Hawaii], August 3, 1956. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tht19560803-01.1.1&srpos=22&e=——-en-10–21–img-motokane——–.

“Information on McKinley War Dead Is Sought.” Hawaii Times [Honolulu, Hawaii], November 26, 1947. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tht19471126-01.1.4&srpos=102&e=——-en-10–1–img——-.

Ishimoto, Arthur. Oral history interview by Richard Hawkins. Japanese American Military History Collective. October 12, 2010. ndajams.omeka.net/files/show/8430.

“Japanese Boys’ Resume Games After 2 Weeks.” Nippu Jiji [Honolulu, HI], March 10, 1930. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tnj19300310-01.1.10&srpos=88&e=——-en-10–81–img-motokane——–.

“Japanese High Graduates 288.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], June 16, 1930. Newspapers.com (275021284).

Jitsugyō no Hawai. Industrial Magazine. September 1, 1941. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=jnh19410901-01.1.406&e=——-en-10–1–img-motokane——–.

“Legal Notices.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], December 29, 1943. Newspapers.com (275631330).

MacArthur in Japan: The Occupation: Military Phase. U.S. Army Center of Military History. https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/macarthur%20reports/macarthur%20v1%20sup/.

“Marriage Applications.” The Honolulu Advertiser [Honolulu, Hawaii], February 25, 1937. Newspapers.com (264998935).

“Martha Tamura to Present 36 Pupils In Piano Recital.” Hawaii Times [Honolulu, Hawaii], April 29, 1950. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tht19500429-01.1.2&srpos=2&e=——-en-10–1–img-motokane+hongwanji——–.

“Mary Manabe.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], January 4, 1989. Newspapers.com (272614037).

Masatsugu, Michael Kenji. Reorienting the Pure Land: Japanese Americans, the Beats, and the Making of American Buddhism, 1941-1966. Dissertation. University of California, Irvine, 2004.

Matsunaga, George. Oral history interview by Richard Hawkings. Japanese American Military History Collective. October 9, 2010. ndajams.omeka.net/files/show/1050.

“Mick Seniors’ Dance Tonight.” Nippu Jiji [Honolulu, HI], April 21, 1933. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tnj19330421-02.1.9&srpos=107&e=——-en-10–101–img-motokane——–.

Mitsuno Sumida Motokane. Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. Arriving and Departing PAssenger and Crew Lists, 1900-1959. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

“Most Worthy Cause by 442nd.” Hawaii Times [Honolulu, Hawaii], October 25, 1949. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tht19491025-01.1.2&srpos=51&e=——-en-10–51–img-motokane——–.

“Motokane Heads Class.” Nippu Jiji [Honolulu, HI], March 1, 1930. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. https://hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tnj19300301-01.1.10&srpos=20&e=——-en-10–11–img-motokane——–.

Motokane, Jr., Wilfred Masao. E-mail interview by the author. August 22, 2022.

Motojiro Motokane. Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. Arriving and Departing Passenger and Crew Lists, 1900-1959. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Muneto, Tatsuo. E-mail interview by the author. February 21, 2022.

“Nishikaya Beats Y.M.B.A. 22-2, In Boys’ League.” Nippu Jiji [Honolulu, HI], March 12, 1929. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tnj19290312-01.1.13&srpos=37&e=——-en-10–31–img-motokane——–.

“Obituaries.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], October 17, 1950. Newspapers.com (280909485).

“Outdoor League Starts Saturday.” Nippu Jiji [Honolulu, HI], January 14, 1930. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tnj19310304-01.1.12&srpos=41&e=——-en-10–41–img-motokane——–.

Rev. Horyu Asaeda of the Liliha Shingonji Mission being fingerprinted by the MPs at the Honolulu immigration station, soon after his arrest. Photograph. Folder 272. JIR Files. University Archives & Manuscripts Department, University of Hawaii at Manoa Library.

“Roosevelt and McKinley To Open Interscholastic Debating Series.” Nippu Jiji [Honolulu, HI], January 26, 1932. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tnj19320126-01.1.10&e=——-en-10–101–img-motokane——-.

Sadao Motokane. Hawaii State Archive. Birth Certificates and Indexes. Honolulu, HI, USA. Digital Image. ancestry.com.

Sadao Motokane. World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947. Digital images. ancestry.com.

“Second Group At McKinley Get Diplomas.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], June 8, 1933. Newspapers.com (275073291).

“Senior Committees Named.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], October 21, 1932. Newspapers.com (274851810).

“Sgt. W. M. Motokane Killed on Okinawa When Plane Crashes.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], August 29, 1945. Newspapers.com (276153978).

“Sgts. Kuwada and Motokane Killed in Okinawa Crash.” Hawaii Times [Honolulu, Hawaii], August 29, 1945. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tht19450829-01.1.2&e=——-ja-10–1–img——-.

“Shafter Service Wins 11th Straight In Amateur League.” Nippu Jiji [Honolulu, HI], February 18, 1936. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tnj19360218-01.1.4&srpos=58&e=——-en-10–51–img-motokane——.

Shizuko Motokane. Hawaii, U.S., Birth Certificates and Indexes, 1841-1944. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

“Swimmers Honor Nisei War Dead.” Hawaii Times [Honolulu, Hawaii], August 24, 1949. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tht19490824-01.1.1&srpos=99&e=——-en-10–1–img——-.

“Three Oahu Youths Named To Air Academy.” Hawaii Times [Honolulu, Hawaii], May 17, 1955. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tht19550517-01.1.1&srpos=10&e=——-en-10–1–img-motokane——–.

“Violet Teruko Hoshibata.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], February 9, 2008. Newspapers.com (274229609).

“Widow Killed By Bus on Way To Wake Here.” Hawaii Times [Honolulu, Hawaii], August 10, 1954. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tht19540810-01.1.1&srpos=4&e=——-en-10–1–img-motokane——–.

Wilfred M. Mokotane. Photograph. 1933 McKinley High School Yearbook. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Wilfred M. Motokane. Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S., National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl), 1941-2011. Digital images. ancestry.com.

Wilfred M. Motokane. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Wilfred Masao Motokane. World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947. Digital images. https://anecstry.com.

“Will Assist Boys.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], October 17, 1931. Newspapers.com (274976789).

“Yoshiko Urata.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin [Honolulu, Hawaii], January 22, 1997. Newspapers.com (273872183).

Secondary Sources

“442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT).” Neisei Veterans Legacy. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.nvlchawaii.org/442nd-regimental-combat-team/.

Asato, Noriko. “The Japanese Language School Controversy in Hawaii.” In Williams, Duncan R. and Tomoe Moriya, Eds. Issei Buddhism in the Americas. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

Bamford, Tyler. “The Most Fearsome Sight: The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima.“ National WWII Museum. Last modified August 6, 2020. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/atomic-bomb-hiroshima.

Barnes, Phil K. A Concise History of the Hawaiian Islands. Hilo: Petroglyph Press, 2013.

“Battalion History.“ 100th Infantry Battalion Veterans Education Center. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.100thbattalion.org/history/battalion-history/.

Blakemore, Erin. “After Pearl Harbor, Hawaii Spent Three Years Under Martial Law.“ HISTORY®. Last modified March 18, 2021. Accessed August 18, 2022. https://www.history.com/news/hawaii-wwii-martial-law.

Croes, Jaered Koichi. “Understanding the Japanese Address System.” Tofugu. Last modified January 6, 2010. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.tofugu.com/japan/japanese-address-system/.

Daniels, Roger. Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans in WWII. New York: Hill and Wang, 1994.

“Dharma Name Homyo.” Buddhist Churches of America. Accessed September 20, 2022. https://www.sfvhbt.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Homyo.pdf.

Frank, Richard B. “‘To Bear the Unbearable’: Japan’s Surrender, Part I.“ National WWII Museum. Last modified August 18, 2020. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/japans-surrender-part-i.

Frank, Richard B. “‘To Bear the Unbearable’: Japan’s Surrender, Part II.” National WWII Museum. Last modified August 20, 2020. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/japans-surrender-military-coup-1945.

“Grace Yoshie Motokane Numazu.“ Find a Grave. Accessed June 1, 2022. www.findagrave.com/memorial/182240043/grace-yoshie-numazu.

Hickox, Will. “WWII Highlights from the Truman Library’s Archives and Collections – Marching to Victory: The Potsdam Declaration July 26, 1945.“ Truman Library Institute. Last modified July 26, 2020. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.trumanlibraryinstitute.org/wwii-75-marching-victory-17/.

“Hiroshima and Nagasaki: 75th anniversary of atomic bombings.” BBC. Last modified August 9, 2020. Accessed September 20, 2022. www.bbc.com/news/in-pictures-53648572.

“Historical Overview.“ National Park Service. Last modified August 17, 2022. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.nps.gov/hono/learn/historical-overview.htm.

“History.“ Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii. Accessed August 18, 2022. hongwanjihawaii.com/history/.

Hiura, Arnold T., and Shuzo Uemoto. From Bento To Mixed Plate: Americans Of Japanese Ancestry In Multicultural Hawai’i. Exhibition. Japanese American National Museum. https://www.janm.org/exhibits/bento.

“Honouliuli Internment Camp.“ National Park Service History eLibrary. Last modified December 2, 2021. Accessed September 19, 2022. npshistory.com/publications/hono/index.htm.

Hunter, Louise H. Buddhism in Hawaii: Its Impact on a Yankee Community. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1971.

Jansen, Marius B., et al. “Japan.” Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Japan.

Kashima, Tetsuden. Judgement without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment During World War II. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003.

Kimura, Katie. “Wilfred Masao Motokane.” In Davy, Lane, Christina Lee, and Zoë E. Sprott, Eds. Pūowaina: Memorializing the Enshrined at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. California: University of Riverside Press, 2021.

“Luzon.” Britannica. Last modified January 23, 2019. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.britannica.com/place/Luzon.

“Manhattan Project: Japan Surrenders, August 10-15, 1945.” U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/Events/1945/surrender.htm.

“Mary Shizuko Motokane Manabe.” Find a Grave. Updated February 10, 2022. Accessed June 1, 2022. www.findagrave.com/memorial/236624707/mary-shizuko-manabe.

McNaughton, James C. Nisei Linguists Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service during World War I. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 2006. history.army.mil/html/books/nisei_linguists/CMH_70-99-1.pdf.

Military Intelligence Service Veterans Club of Hawaii. E-mail interview by the author. March 23, 2022.

“Mitsuno Sumida Motokane.” Find a Grave. Updated AUgust 8, 2017. Accessed June 1, 2022. www.findagrave.com/memorial/182210024/mitsuno-motokane.

“Motojiro Motokane.” Find a Grave. Updated August 8, 2017. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/182210026/motojiro-motokane.

Mullins, Joseph G. Hawaiian Journey. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing, 1978.

Murphy, Thomas D. In Freedom’s Cause: A Record of the Men of Hawaii Who Died in the Second World War. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1949. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/c748bb71-42e0-4c41-adf9-b2abbdf89f75/content.

Nakasone, Edwin M. Japanese-American Veterans of Minnesota. White Bear Lake: J-Press Pub., 2002.

Nishigaya, Linda, and Ernest Oshiro. “Reviving the Lotus: Japanese Buddhism and World War II Internment.” In Falgout, S. and L. Nishigaya, Eds. Breaking the Silence: Lessons of Democracy and Social Justice from the World War II Honouliuli Internment and POW Camp in Hawai‘i. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i, 2014: 173-198. http://dspace.lib.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10790/4429/1/nishigaya.l-2014-0001_ocr.pdf.

Okihiro, Gary Y. Cane Fires: The Anti-Japanese Movement in Hawai’i. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991.

Oshiro, Seiki, Paul Tani, and Grant Ichikawa. Military Intelligence Service Language School Registry 1941-46. Japanese American Veterans Association. Accessed August 18, 2022. www.javadc.org/MISLS%20Registry%2002-02-03.pdf.

“Pearl Harbor Attack.” Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed August 18, 2022. www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1941/pearl-harbor.html.

“Photos.” 442nd Regimental Combat Team Legacy Website. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.the442.org/photos2.html.

“The Potsdam Conference, 1945.” Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State. Accessed September 19, 2022. history.state.gov/milestones/1937-1945/potsdam-conf.

“Shin Buddhist Holidays.” Wahiawa Hongwanji Mission. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.wahiawashinbuddhists.org/shin-buddhist-observances.

Soga, Yasutaro. Life Behind Barbed Wire: The World War II Internment Memoirs of a Hawaii Issei. Translated by Kihei Hirai. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

“Special Observances.” Berkeley Buddhist Temple. www.berkeleybuddhisttemple.org/special-observances.

Tanaka, Kenneth Kenichi. Ocean: An Introduction to Jodo-Shinshu Buddhism in America. Berkeley: Wisdom Ocean Publications, 1997.

“TEC4 Wilfred Masao Motokane.” Find a Grave. Updated August 6, 2020. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56126391/wilfred-m-motokane.

“Temple History.” Honpa Hongwanji Hawaii Betsuin. Accessed August 19, 2022. hawaiibetsuin.org/temple-history/.

“Timeline.” 100th Infantry Battalion Veterans Education Center. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.100thbattalion.org/history/battalion-history/.

“The Untold Story.” The Untold Story: Internment of Japanese Americans in Hawaii. Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii. Accessed September 19, 2022. www.hawaiiinternment.org/untold-story/untold-story.

“Victory in the Pacific: Japan’s Surrender and Aftermath.” Naval History and Heritage Command. Last modified September 2, 2021. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1945/victory-in-pacific.html.

“Wilfred Masao Motokane.” National Cemetery Administration Grave Locator. https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/ngl/index.jsp.

Williams, Duncan Ryuken. American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2019.

Williams, Duncan Ryuken. “Complex Loyalties: Issei Buddhist Ministers during the Wartime Incarceration.” Journal of Buddhist Studies no no. 5 (2003). http://enlight.lib.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-MAG/mag148972.pdf.

“Yoshiko Motokane Urata.” Find a Grave. Updated August 15, 2017. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/182411352/yoshiko-urata.