Colonel William Andrew Lee

- Unit: 5th Marine Brigade, 13th Regiment, Company K (World War I)

- Date of Birth: November 12, 1900

- Entered the Military: May 22, 1918

- Date of Death: December 29, 1998

- Hometown: Ward Hill, Massachusetts

- Award(s): Navy Cross (3), Purple Heart (3), Nicaraguan Medals of Valor (Cruz de Valor) with Palm (2)

- Cemetery: Section 17, Site 994. Quantico National Cemetery, Triangle, Virginia

Park View High School

2017–2018

Before the War

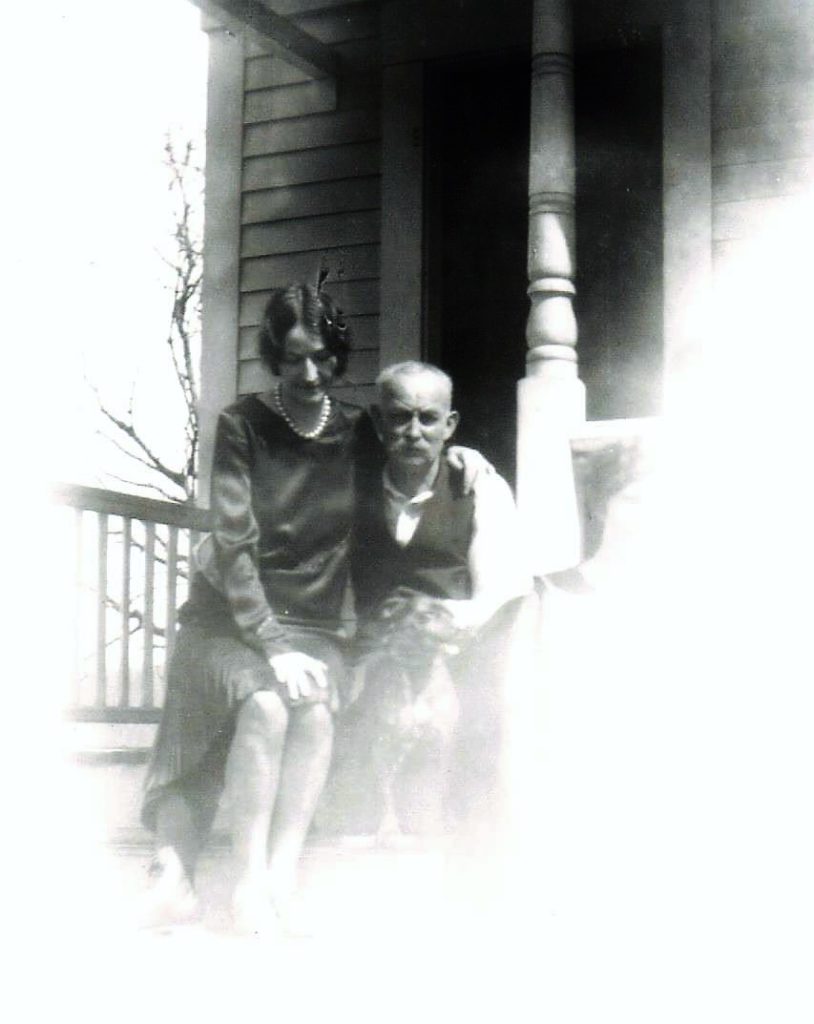

William “Ironman” Lee was born in Ward Hill, Massachusetts, to Benjamin and Eda Lee on November 12, 1900. Benjamin worked as a stationary engineer at Knipes Shoe Factory, and Eda worked to keep the household in order as William was joined by four other siblings: George, Francis, Robert, and Joseph.

Lee’s father, Benjamin, grew up outside Asheville, North Carolina, so the family would make yearly trips to the area. On these trips, Lee spent a considerable amount of time at the Cherokee Indian Reservation where he learned many of the skills that would help to keep him alive during his time in the U.S. Marine Corps. The Cherokee taught Lee how to hunt, stalk, live off the land, track animals, shoot, and use a knife.

Though the outdoors were an important aspect of Lee’s formative years, education was also considered vital within the family. Eda read Lee poetry instead of bedtime stories. Lee also took advantage of his extended family to help his education. His uncle, a well-known doctor in the area, taught Lee the equivalent of two years of medical school before he completed high school. Lee also visited with neighborhood families, where he became fluent in Spanish and learned from professors from both the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.) and Harvard University. Throughout this time, Lee became a star fullback on his high school football team.

Military Experience

William “Ironman” Lee was born in Ward Hill, Massachusetts, to Benjamin and Eda Lee on November 12, 1900. Benjamin worked as a stationary engineer at Knipes Shoe Factory, and Eda worked to keep the household in order as William was joined by four other siblings: George, Francis, Robert, and Joseph.

Lee’s father, Benjamin, grew up outside Asheville, North Carolina, so the family would make yearly trips to the area. On these trips, Lee spent a considerable amount of time at the Cherokee Indian Reservation where he learned many of the skills that would help to keep him alive during his time in the U.S. Marine Corps. The Cherokee taught Lee how to hunt, stalk, live off the land, track animals, shoot, and use a knife.

Though the outdoors were an important aspect of Lee’s formative years, education was also considered vital within the family. Eda read Lee poetry instead of bedtime stories. Lee also took advantage of his extended family to help his education. His uncle, a well-known doctor in the area, taught Lee the equivalent of two years of medical school before he completed high school. Lee also visited with neighborhood families, where he became fluent in Spanish and learned from professors from both the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.) and Harvard University. Throughout this time, Lee became a star fullback on his high school football team.

Military Experience

Lee’s first attempt to join the military ended in disappointment. He and several of his friends went to the U.S. Army recruiting station in hopes of joining the 42nd (Rainbow) Division and see some action before the First World War ended. The recruiter turned 17-year-old Lee away because he was too young.

Lee tried the Marine recruiting office and was told that if he could get his father to sign the paperwork, he could enlist. In a defiant spirit that would define Lee’s military career, he asked the first man he saw to sign the forms in his father’s name. On May 22, 1918, Lee enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps and reported to Marine Barracks, Parris Island, South Carolina.

After boot camp, Lee was sent to Machine Gun School at the Savage Arms Plant in Utica, New York. By September 1918, Lee shipped out to France and was assigned to Company K, 13th Regiment of the 5th Marine Brigade where he quickly rose to the rank of corporal. While in France, Lee and the men of the 13th Regiment were based in Brest, France, a major disembarking port for American forces.

As the war ended, Lee and the members of the 13th Regiment were sent to Nantes, France, to perform various duties. They served as military police, guarded camps and hospitals, helped with supply distribution, and transported sick or wounded soldiers to ships bound for the United States. In August 1919, Lee returned to the United States and consequently decided to leave the Marines due to the slow rate of promotion.

In September 1921, Lee reenlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps after many of the higher enlisted ranks were cleared of career Marines. Over the next five years, Lee served as part of the Marine detachment aboard the USS Arkansas. Marines on naval vessels ran the brig (military jail), protected the ship, and provided security for the captain of the ship in the event of a mutiny or other crisis.

In 1924, Lee and the other Marines formed a rowing team and won the Dunlop Cup. Lee also became the Heavyweight Boxing Champion of the fleet while aboard the Arkansas. Lee steadily rose through the ranks, reaching gunnery sergeant by April 1925. Gunnery Sergeant Lee also made a name for himself during this time by qualifying as an expert marksman with almost every weapon he tried. Lee later reflected in an interview that his time on the USS Arkansas were his best years in the Corps because he was able to serve alongside his brother, George.

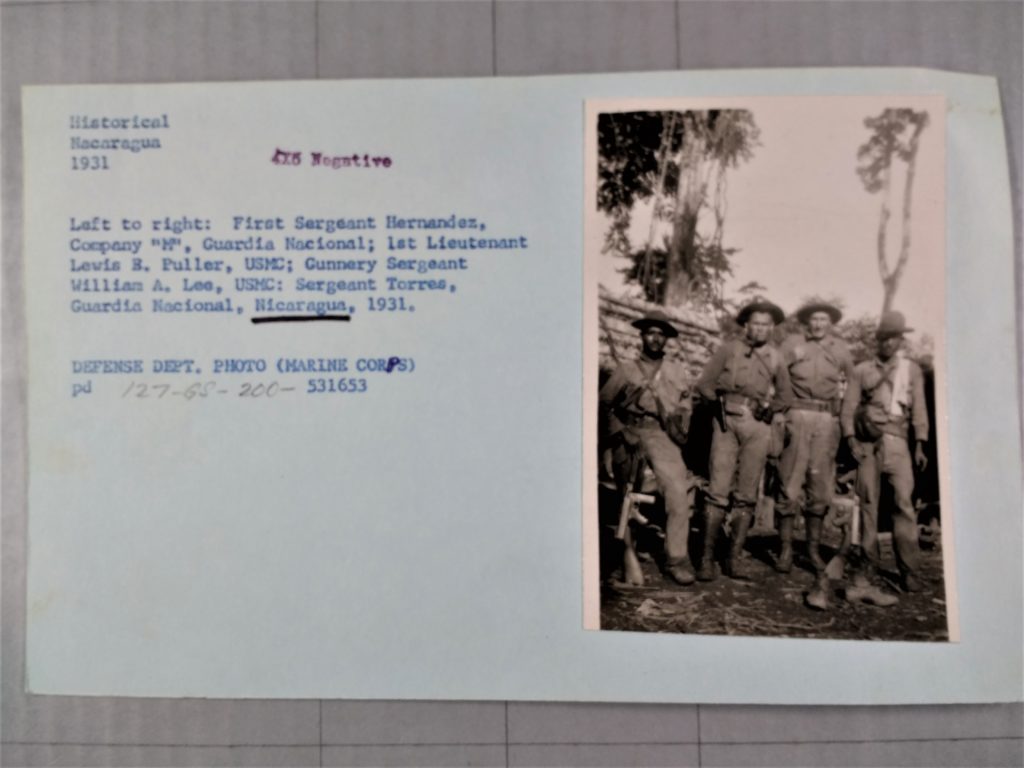

In early 1927, Lee was shipped to Central America to take part in the occupation of Nicaragua. Over the next several years, Lee led countless patrols, engaged with rebel forces, trained the Nicaraguan National Guard, and ran supply depots. Early in his deployment to Nicaragua, Lee was challenged to a knife duel by an angry local and after receiving a severe cut on his leg, he killed the man. This would be just one of many knife fights that Lee would survive.

On September 26, 1932, while on patrol with Captain Chesty Puller, who would go on to fame in his own right, Lee showed the type of tenacity that would earn him the nickname “Ironman.” The Marines and Nicaraguan National Guard were ambushed by roughly 150 rebels. In the opening moments of the fight, Lee was shot in the head, lost consciousness, and was left for dead. Lee’s actions thereafter solidified his status as a warrior. An excerpt from his Navy Cross citation reads:

…Lee was wounded twice and became unconscious in the early stages of the combat. After a period of from fifteen to twenty minutes he recovered consciousness and in spite of his weakened condition, with disregard for his personal safety, he moved the Lewis Machine Gun to a better fire position, used it with destructive effect, resumed his duties as Second in Command, and went forward in the final attack on the enemy position.

After the firefight, Lee and his patrol walked 125 miles back to base, fighting through several other ambushes. In Nicaragua, Lee was awarded three Navy Crosses, three Purple Hearts, and two Nicaraguan Medals of Valor (Cruz de Valor) with Palm. Lee’s fighting ability was so legendary among the rebel forces that they allegedly put a $50,000 bounty on his head.

When Lee returned to the United States in January 1933, he spent six months at the U.S. Naval Hospital in Washington D.C., recovering from multiple wounds and suffering from a bad case of malaria. By June, Lee was stationed at Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia, and in August 1934, he reported to Ordinance Field Service School at Raritan Arsenal, Metuchen, New Jersey. After completing training, Lee was promoted to the rank of Marine Gunner and spent the next five years assigned to the Fifth Marines in various roles. During this time, Lee took part in several pistol and rifle shooting competitions.

On August 26, 1939, Lee was shipped to the port city of Qinhuangdao and was assigned to the U.S. Embassy in Peiping (now Beijing), China. U.S. Marines in China were ordered to protect American civilians and U.S. government property during the Chinese Revolution and the Second Sino-Japanese War.

With tensions between the U.S. and Japan escalating, the majority of the Marines stationed in China were withdrawn to Corregidor, a small island at the mouth of Manila Bay in the Philippines, in November 1941. However, Lee and a small detachment of Marines remained at the embassy in Peiping. On December 7, (December 8 in China) the Japanese launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and moved to capture the American Embassy in Peiping.

According to eyewitness accounts, as the Japanese approached the compound, Lee prepared machine guns, small arms, and ammunition for the defense of the embassy. With about twenty Marines to support him, Lee planned to fight thousands of Japanese troops to the death. The Marines received orders to stand down and not resist. Approximately 200 Marines and sailors in the Peiping area were taken prisoner just two days before they were set to join the rest of the 4th Marine Regiment on Corregidor Island.

The Marines were transferred to Korea where they boarded ships and were sent to Japan. Once in Japan, the POWs were taken to Hokkaido Internment Camp, on the northernmost island of the Japanese archipelago. During his time as a POW, Lee was savagely beaten by guards due to his size and his demands for better living conditions for his fellow POWs. Frequently, the Japanese guards would put lit cigarettes out on his ears and, on one particularly severe incident, a Japanese soldier kicked Lee’s teeth out.

After the atomic bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, many of the guards fled the camp. Once Lee and the other POWs figured this out from a guard who spoke some English, they decided that those strong enough needed to take over the camp in case the remaining guards attempted to kill everyone. Lee recalled in an interview about coming face to face with one of the more “evil ones” who had sadistically beaten him several times. Lee killed the guard and helped to capture and hold the camp until the American military arrived. Lee and his comrades were officially POWs until Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945. The Marines guarding the embassy are the longest recorded American POWs of the Second World War.

Upon his release, now Second Lieutenant Lee reached San Francisco, California, on September 22, 1945 and spent the next several weeks at a U.S. naval hospital recovering. Over the next several months, Lee received a steady stream of promotions he earned during his time in the internment camp as the Marines continually issued promotions to POWs. Lee was promoted to lieutenant colonel in July 1946, and eventually commanding officer of rifle range at Camp Lejeune, in North Carolina. Lee spent the next four years in charge of the rifle ranges until he retired as a full colonel from the Marine Corps on July 1, 1950. Of Lee’s 32 years of service, he spent an incredible 22 years on overseas duty.

Veteran Experience

In the spring 1949, Helen, Lee’s first wife, died, which impacted his decision to retire. Lee devoted himself to raising his three daughters, Edith, Nancy, and Linda. As the conflict in Korea heated up, he attempted to return to the Marines but he was too old for active service.

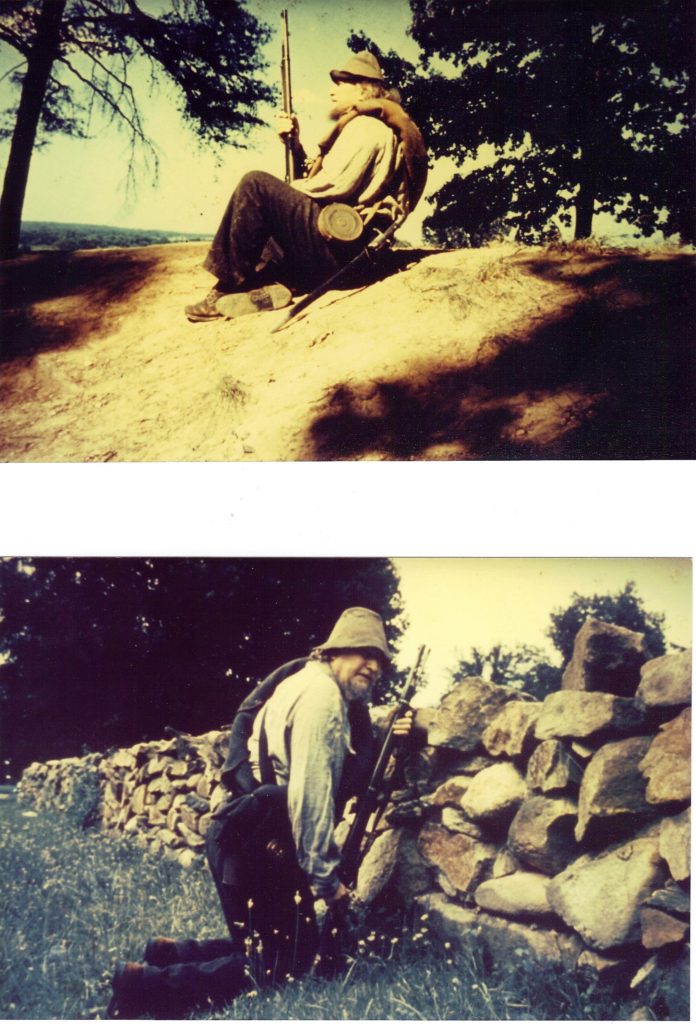

Besides caring for his daughters, Lee took part in many competitive shooting competitions and became an active member in Civil War reenactments and a local Civil War Round Table in Fredericksburg Virginia. It is at one of the Round Table meetings that Lee met Ann and the two married in 1962. In 1964, Ann and Lee welcomed a daughter, Beverly, to their family.

Lee poured his energy into many historical organizations, speaking at events for groups like the Order of the Purple Heart and the Navy League, attended various Marine Corps Balls, and actively worked in the local community.

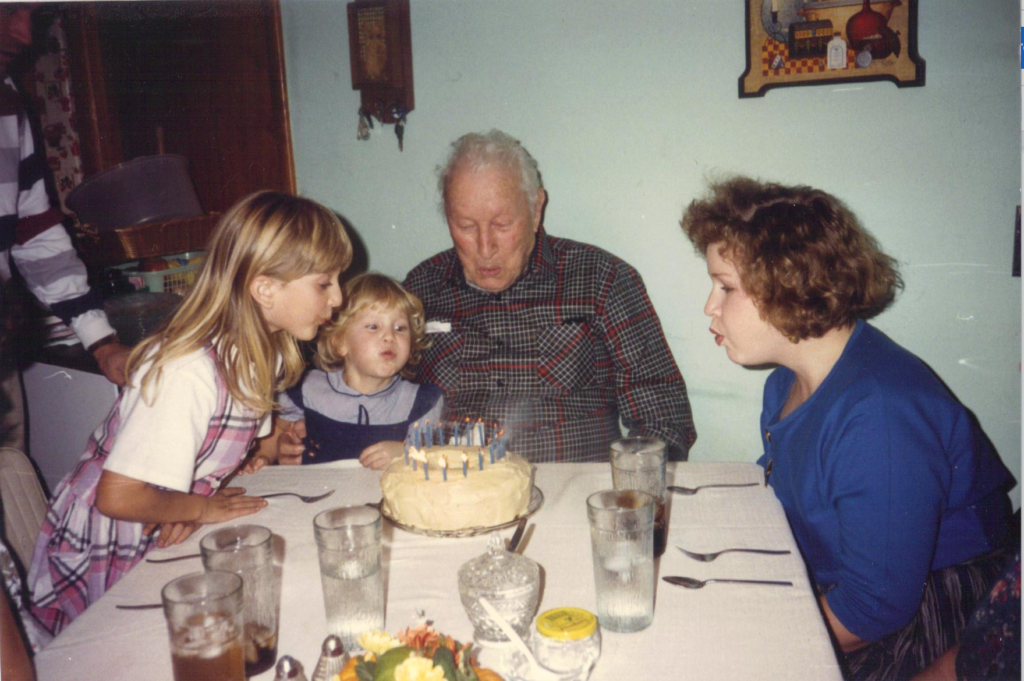

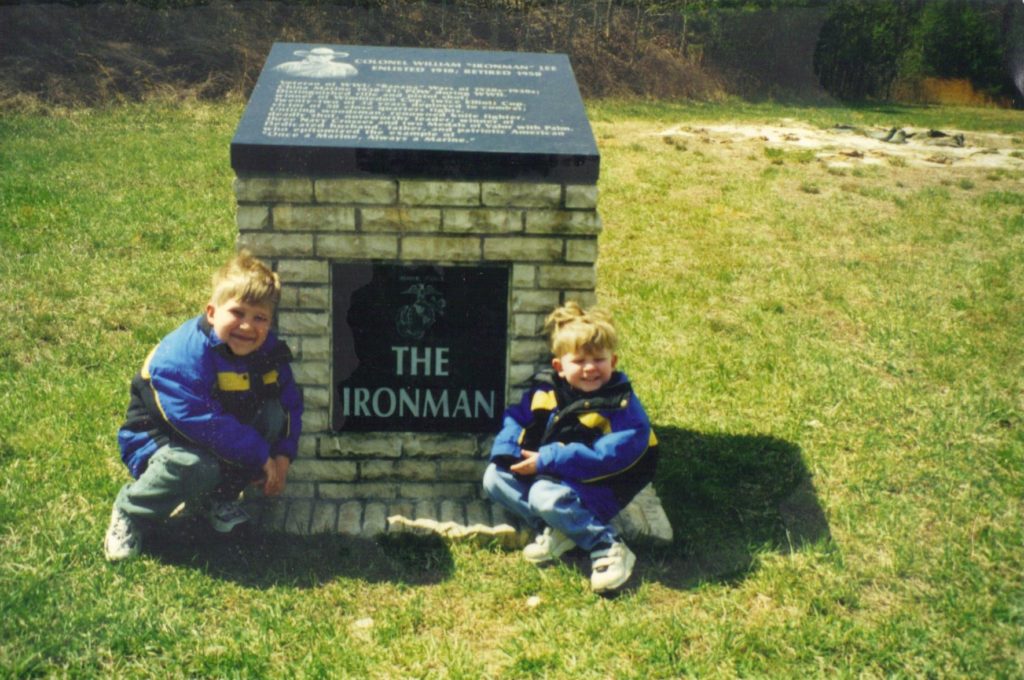

At the age of 95, the Ironman showed that he still lived up to his title. Lee attended a ceremony at Marine Corps Base Quantico where a new, high tech range was being dedicated in his honor. When Lee had a chance to say a few words he told the crowd that he would like to fire the Marines current issued rifle, the M-16A2. After taking off his blazer, he fired a total of nine rounds at moving targets which were about 30 yards away. Unsurprisingly, he hit all nine targets.

Commemoration

At the age of 98, Lee died of cancer at Mary Washington Hospital in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

At the time of his death, Lee was survived by his second wife, Ann Bradbury Lee, four daughters, three stepsons, 11 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. He is buried at Quantico National Cemetery, section 17, plot 994.

Ann, whom Lee would often refer to as his “Guiding Angel,” summed up Colonel Lee’s life best when she said, “One man just can’t do all he has done in one lifetime, but he did.”

Bibliography

2nd Brigade, Reports Received from Marine Units in Nicaragua, 1927–1932; Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Adjutant and Inspector’s Department, Record Group 127 (Box 5); National Archives, Washington, D.C.

U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798–1958. Digital images. http://ancestry.com.

Bartlett, Tom. “The Ironman.” Leatherneck, July 1984, 18–23.

Bartlett, Tom. “The Ironman.” Leatherneck, August 1984, 24–31, 62.

Bartlett, Tom. “The Ironman.” Leatherneck, September 1984, 24–29,63.

Officer Files, 1920–1932, Nicaragua; Guardian National, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127 (Box 1); National Archives and Records Administration.

Lee, Ann. In person interview. August 7, 2018.

Left to right: First Sergeant Hernandez, Company “M”…Gunnery Sergeant William A. Lee, USMC…. Photograph. 1931. National Archives and Records Administration (127-GS-200-531653). Image.